(WARNING: While there are no pictures of animal slaughter in this post, detailed photos of an intact, dressed lamb carcass might nevertheless disturb sensitive readers. Please scroll carefully.)

About ten days ago I bought a whole lamb and butchered it; it was what I wanted to do for my birthday. I cooked it in four ways and packaged a lot of it for the freezer.

The idea for all this came from a wonderful dinner on Good Friday of this year in Fitou with my friends and landlords Christine and Hagen. It was still the off-season and only one of Fitou’s four restaurants was open, not counting the pizzeria. The plat du jour that night was lamb prepared three ways, and I’ve dreamt of this plate of food ever since.

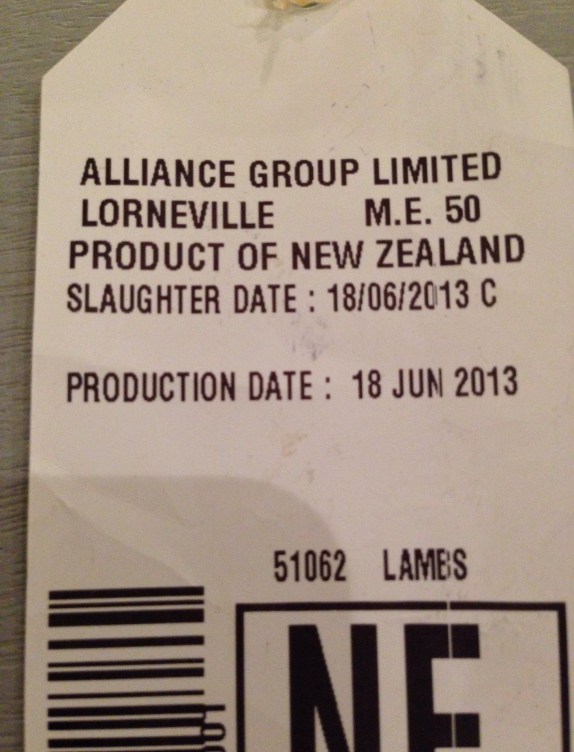

I decided to go a step beyond simply reproducing the meal, thus my whole animal. After some research I settled on a small family-run market in Northridge, Calif., called, appropriately, Family Market. They supply halal meats and Middle Eastern groceries and offered entire lambs, both from New Zealand and of local origin. The imports were cheaper and smaller so that’s what I ordered.

While it might seem counterintuitive that meat from the other side of the world would be cheaper than the equivalent raised just a few miles away, lamb is such a universal commodity there that it’s far less expensive, even when shipped. In the US, per capita lamb consumption is less than a pound per year; in New Zealand the figure is almost 60 pounds.

I knew vaguely that halal is a religious term indicating the permissibility of certain foods in Islam and, in this case, the procedure used during the animal’s slaughter, but I was surprised by the degree to which ritual plays a part. Similar in practice to kosher, the halal slaughter follows a strict set of rules intended both to make the event as humane as possible and to honor God/Allah.

The slaughter occurs where the animal cannot see or be seen by other animals. The animal and the person doing the slaughtering are oriented to face Mecca. If the animal becomes agitated it is released from the enclosure until the next day. The knife must be sharp, but not sharpened in front of the animal. It is given water. It is turned onto its side or back and kept calm, partly by the repetitive chanting of “Bismillah Allahu-Akbar” (In the Name of Allah).

I watched numerous videos of this process and became convinced that it presents the most humane possible method of dispatching the animal.

At just 27 pounds, my lamb was small, making it more manageable to carry home and then disassemble in my modest kitchen. Incidentally, he entered the United States through the Port of San Diego, reminding me that we need to go down there for a weekend sometime soon.

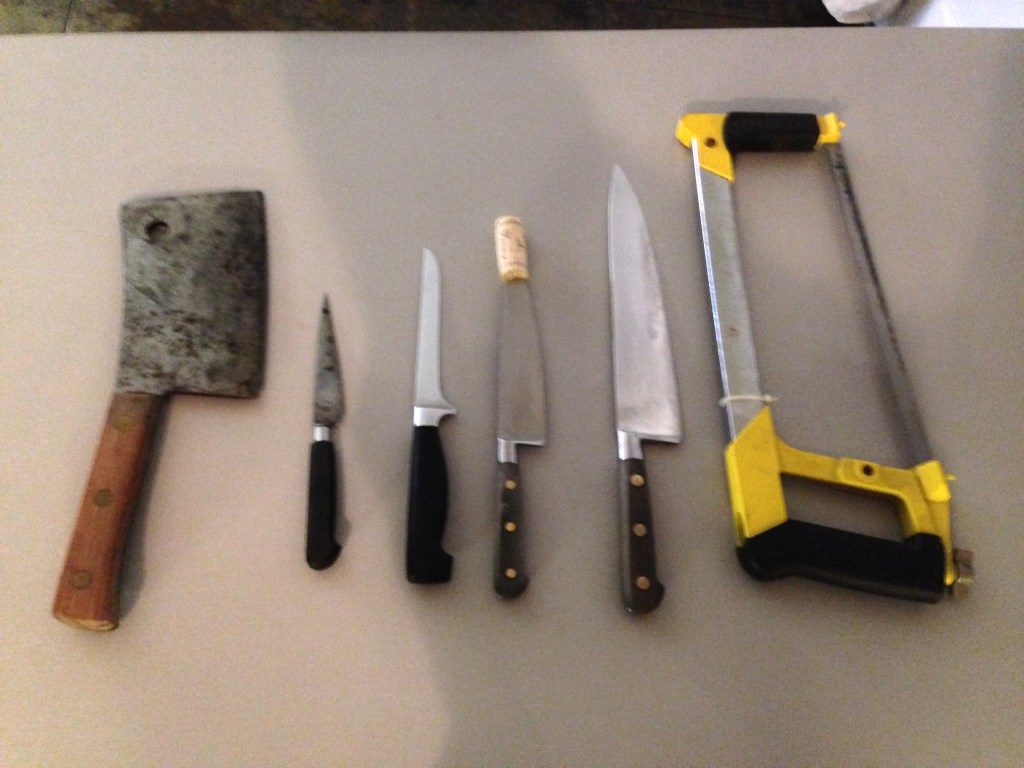

I had spent many hours viewing YouTube videos and other Internet guides to butchering a lamb and began the process with confidence. I had cleared off the kitchen island and sharpened my knives and cleaver. I did not buy a meat saw but used my hacksaw, after cleaning it thoroughly.

First we got acquainted.

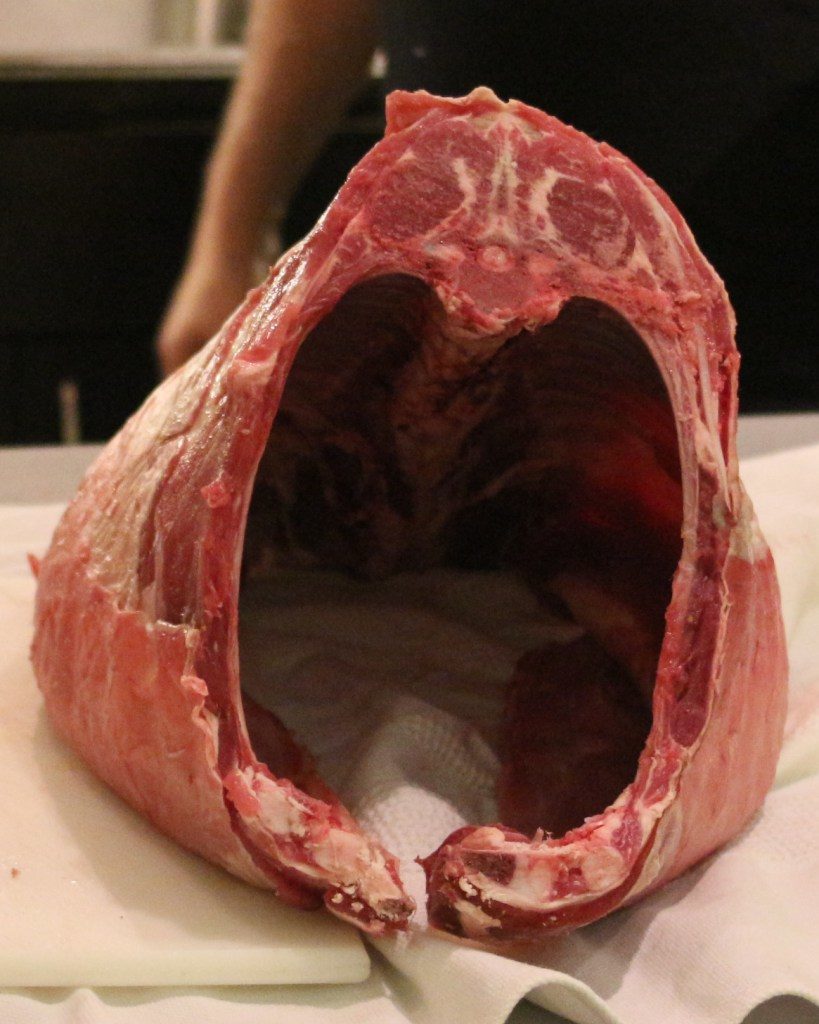

Then an examination from stem to stern.

The first task was to break the carcass down into four main sections, the so-called primal cuts: the shoulder (including neck and foreshanks), the rack (with breast), the loin (with flank), and the leg. Once these initial cuts were made the pieces could fit in the refrigerator and I could take my time with the rest of the job.

The head, by the way, does not arrive with imported lambs. I did not miss it.

The separation of the front end was easy. I counted five ribs back from the front, made cuts behind them up from either side of the spine, then sawed easily through the sternum. Another saw through the spine, and voila! The animal’s front end was detached and ready for further breaking down.

The next operation was to move back to the hind end of the loin and cut away the legs and sirloins. The instructions I’d watched and read all said that the easiest way to know where to separate was to feel for the hip bones and cut just in front of them. Several times before the main event, while petting one or the other of our cats, I had lingered over the smalls of their backs, feeling the hips. Calvin thought this was impolite at best so I stopped but I’d already learned what I needed to know. Once I compared what I’d felt on Jenny’s and Riley’s backs with skeletal diagrams the actual cut on the lamb was easy.

I sawed off the trotters to use for stock.

I boned and butterflied one of the legs for marinating and grilling and left the other intact. One day it will make a very delicious Sunday joint.

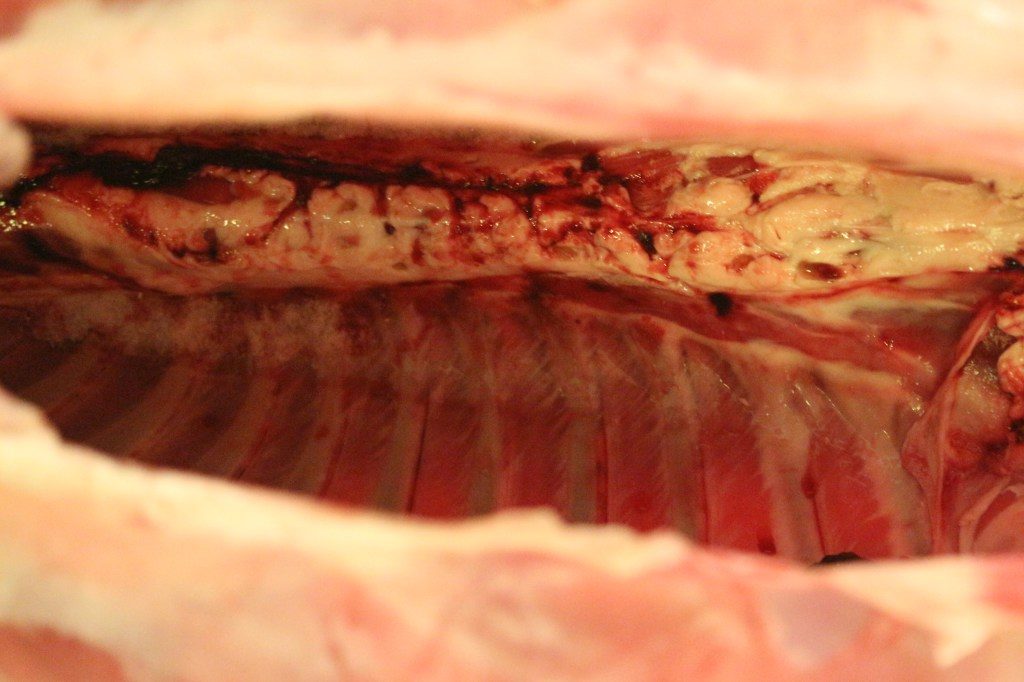

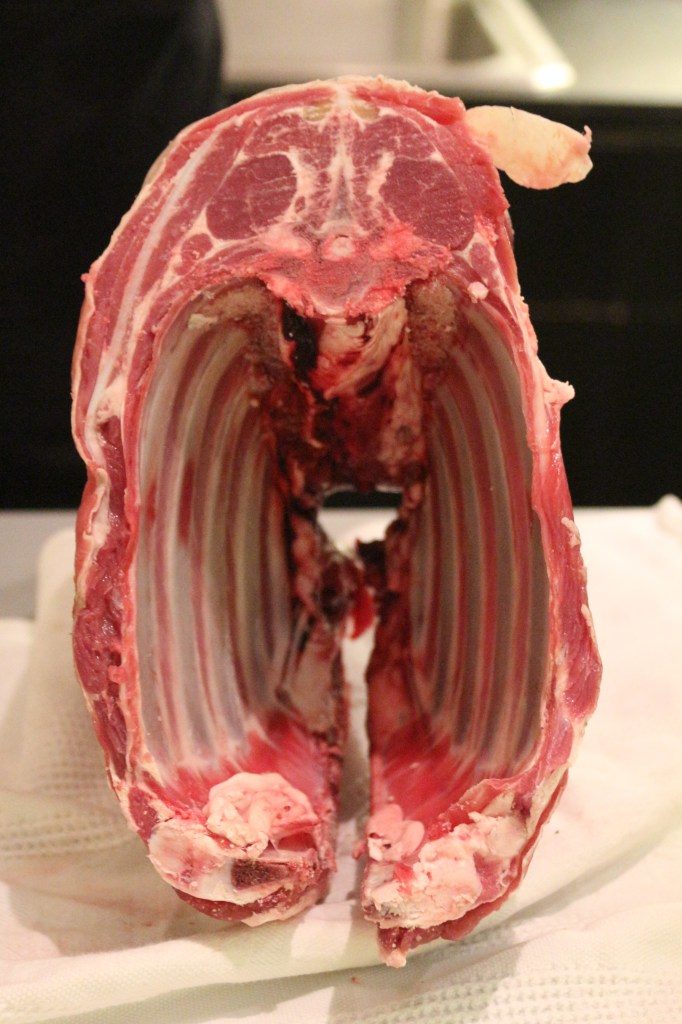

If you’ve bought or cooked lamb you probably know that there are rib chops and there are loin chops. The rib chops, if not separated from each other, make up the racks – one on each side of the animal. Here is the view from the front of the racks, looking back toward the tail. A rib chop on its own resembles a comma.

The layer of meat hugging the ribs is the breast in front, turning into the flank at the rear. (In beef this would become the skirt and flank steaks.) Because my lamb was small I cut much of this away for grinding, but in larger animals the breast could be stuffed and roasted or braised. The ribs were saved to be roasted and added to the stock pot.

At the rear end of the racks, after the 13th pair of ribs, is the loin. For the sake of comparison, the beef equivalent of the lamb racks is prime rib, and the beef equivalent of the loin is, well, the loin. Lamb loin chops are cut crosswise from this section, just as T-bone and Porterhouse steaks are cut from the beef loin.

I chose not to turn my lamb loins into chops because that would have required a lot of difficult sawing. Instead I excised the entire muscles – a loin and a tenderloin on each side – and saved them for what will be a meal of exceptional delectability.

Here I am demonstrating where the loin would be if it were a part of my own body.

And here are those tender, beautiful muscles. Combined they don’t weigh over six or eight ounces.

I mentioned using most of the breast and flanks for grinding, but I reserved two elegant little flaps of meat for schnitzel.

It is of course possible for one lamb to yield four shanks. On the hind legs, though, I opted not to remove them in order to leave as much meat as possible on the legs. Still, the two foreshanks are quite pretty. I’ll braise them with lentils.

This blog post is not a cooking lesson so I will save a report on that subject for later.

My exercise in lamb butchery proved interesting and enlightening but it is one of those things I’ll enjoy having done but won’t need to do again. I made phyllo by hand once and that’s in the same realm. I have not consumed the eyeball of anything larger than a smelt but if I do I expect to feel the same way about it as I do about my lamb.

(The process above was documented photographically by Los Angeles artist Matt Carter. He is working on an upcoming solo show entitled Clearly this slaughterhouse turned nightclub holds many dark secrets. The crisper and better-composed pictures here were taken by Matt, and I am grateful for his participation.)