It was a month after I turned 18 that my mother took me to Las Vegas to see Frank Sinatra. It was November 11th, a Sunday, or really the wee hours of Monday the 12th since the show was at 12:15am. (What was the :15 about?) I had been a huge fan since I was 12 or 13 — when I discovered our soundtrack album to “Pal Joey,” with “The Lady is a Tramp” and “Bewitched” on it — so this was a hugely special post-birthday gift.

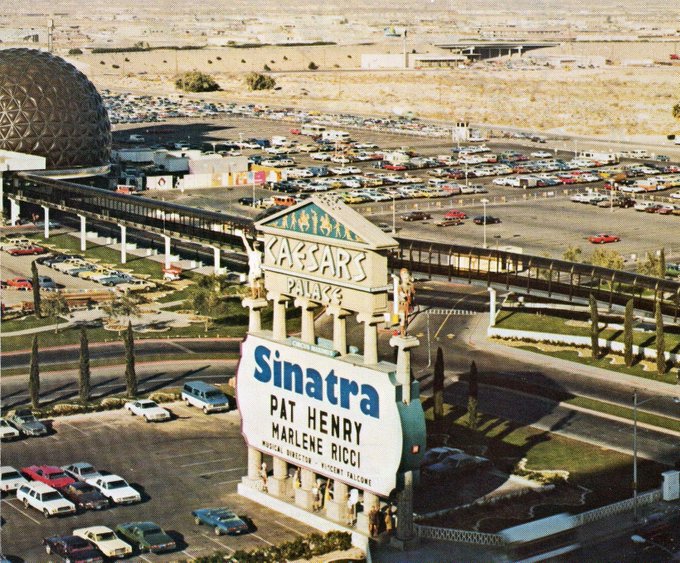

The Caesars Palace billboards around town proclaimed “He’s Here,” and in 1979 everybody knew what that meant. At $35 for a cocktail show it was the most expensive show in town. My dad knew somebody who knew somebody who got my mom and me reservations for the otherwise sold-out performance. We flew from Texas in the morning. It was mild in Las Vegas in the midday but turned chilly that evening in the desert.

Because the Sinatra show didn’t start till 12:15, we had time to catch a dinner show before. It was my birthday-ish so it was my choice between Liberace (at the Hilton, where we were staying), Wayne Newton and Jerry Lewis. I kind of wish that I’d seen Liberace once in my life, but I went for Jerry Lewis at the Sahara, where his show, with opening act Diahann Carroll and with dinner, was $28.50. I’m glad now to have seen Jerry Lewis perform, and I recall that Miss Carroll wore a lot of sequins and feathers. Jerry Lewis was quite tall and he did his typewriter number.

(The Hilton was an exciting place to stay because it figured prominently in Diamonds Are Forever, which was and is my favorite James Bond movie.)

We arrived at Caesars well before showtime and were happy to find ourselves only a few dozen people back from the front of the line. We were happy, at least, until we noticed a second line forming from a sign marked “Invited Guests.” That line grew and grew.

Once the Invited Guests were in, our line snaked toward the showroom. At the maître d’ station we gave our name. The tuxedoed man noted our reservation in his book, then stepped back a few inches and looked down the center aisle, making eye contact with a burly fellow standing in that aisle near the stage. Seeing no acknowledgement from the man in the aisle that Mama and I were deserving of ringside seats, the maître d’ sent us with a waiter to our rightful places. This all happened within a second or two.

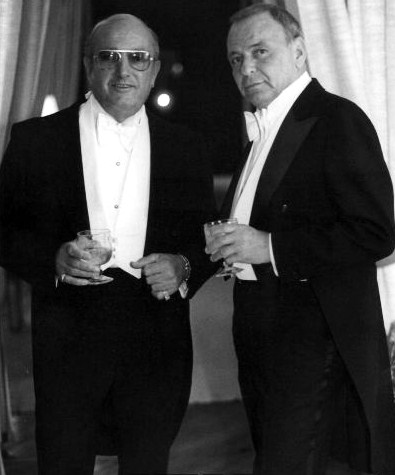

I realized afterward that the man in the aisle near the stage was Jilly Rizzo, Mr. Sinatra’s — depending on what you heard — best bud, bodyguard or goon-in-chief. Jilly was not someone on whose bad side you’d want to be, if you believe the stories about his temperament and fists.

Before entering the sanctum of the Circus Maximus showroom, Mama had suggested that, wherever they wanted to put us, a few judicious bucks in a waiter’s hand might elevate us, seating-wise. We had 80 dollars between us and she let me do the honors and play the Big Shot. As the waiter showed us to our seats I offered my hand shyly, asking if there might be a better table for us.

He grabbed my fist, peeling my fingers away, one by one, from the four twenties within. In a flash he calculated, then said, “No, you’ll be here.” He wasn’t nasty about it.

They weren’t bad seats, really.

The 35-dollar ticket got you not only a couple hours’ entertainment but two drinks as well. I had ginger ale, which seemed appropriately fancy for the occasion. They brought ice in little plastic buckets. (I read that Sinatra was getting a million a week at Caesar’s in those days, so there must have been some gambling and losing anticipated among the people in the Invited Guests line. The showroom held 980 souls, so ticket sales over a week would have brought in less than a quarter of the headliner’s fee.)

Before the headliner was the comic, and before the comic was the girl singer, in this case someone named Marlene Ricci. I don’t doubt her talent but beyond that I remember only her name.

The comic was Pat Henry. I remember laughing but couldn’t tell you any of his jokes from that night.

There was no introduction of Frank Sinatra, no announcement by Mr. Henry or a Voice of God: “And now, ladies and gentlemen, Frank Sinatra!”

Rather, as the comic exited the stage, the curtain rose. And there, standing at the piano, sipping a whiskey and with his back to the audience, was the man himself. He turned and emerged from the orchestra, which made sense considering his emergence from the Big Bands as a solo artist almost 40 years before that night.

POW! came the downbeat of Nelson Riddle’s classic arrangement of “I’ve Got the World on a String,” and we were off to the races. Click here to see Sinatra singing this very song, in the same room, only a few weeks later during a TV special celebrating his 40th anniversary in show business.

I was pretty numb from the excitement of it all and remember only some of the songs. There were chestnuts like Cole Porter’s “I’ve Got You Under My Skin,” newish things like “Maybe This Time” from Cabaret, and several numbers, including George Harrison’s “Something” and “New York, New York,” from the Trilogy album that would come out a few months hence.

Sinatra always told the audience who wrote and arranged his songs: “Here’s one by Fred Ebb and John Kander with a great arrangement by Mr. Vinnie Falcone, who’s sitting at the piano right here.” (“New York, New York”)

He closed the show either with that one or “My Way,” which I understand he hated. With a few bows and blown kisses, the curtain fell, the lights came on, and everyone left. There had not been a standing ovation, which was a nice thing. Standing ovations seem to be de rigueur these days, which I think weakens their significance. And there was by no means any whistling or whooping.

I saw Mr. Sinatra four more times but there’s always something special about your first time. That was an excellent birthday present.

(I just remembered one of Pat Henry’s jokes. He was telling about some upcoming Caesars engagements — Ann-Margret, Andy Williams — and about Tom Jones he said, “His pants are so tight, the people sitting in the back can tell what religion he is.”)