ROASTED CARROT AND GINGER SOUP

A recent news story involving Robert Iger, who is Chairman and CEO of The Walt Disney Company, prompted me to mention on Facebook that Mr. Iger once complimented me on some roasted carrot and ginger soup I served him. A Facebook friend, who is very likely a real friend as well because I am selective in who I admit to my social media circles, said the soup sounded good and asked for the recipe.

Some years ago, I cooked now and then for another Disney executive, not as high-ranking as Mr. Iger but C-level nonetheless. Mr. Iger and his wife, television journalist Willow Bay, were guests one Saturday evening, and the soup was the first course. I forget the main course, but knowing my former clients, I believe it was something elaborate and sauce-y. I therefore went for an easy-to-do starter, and this soup fit the bill. It can be prepared entirely ahead of time and is variable to a limitless degree, according to the whimsy and schedule of the cook.

First you roast some carrots, which involves nothing more than peeling them — or not, if they’re clean — tossing them with a little olive oil, salt and pepper, spreading them on a sheet pan or in a cast-iron skillet, and putting them in the oven. Do not waste a second cutting your carrots into perfect little disks; do your tossing and roasting just as they come to you, whether skinny or fat, short or long. (I ordered some carrot seeds from France a while back. This particular variety grows not long and slender but round and stumpy like golf balls. I believe we harvested a dozen or so before the varmints found them and discovered how easy they were to pull from the earth.) The timing will vary, but you want there to be some darkness somewhere north of mahogany on them. It’s a good idea to jiggle the pan a time or two during roasting. Oh, and could it really be that you don’t know how hot to make your oven? Write this down: unless a recipe makes a fuss about a certain temperature, go with 350 to 400 and you’ll be fine.

And although the olive oil-salt-pepper treatment is all you need, it would also be quite a good idea to strew some thyme sprigs amid the carrots. You could just as well cut a head of garlic in half — no need to peel — and roast it, too, or a few peeled shallots. You can do this part of the recipe a day or two ahead, in case you’re pressed for time.

Next you want to mush up the carrots, which you can do in a food mill, blender or food processor, or with a hand blender. Whichever method you choose, include the shallots if you used them, or the silken contents of the garlic head, as well as the thyme leaves, which you’ll need to strip from their stems.

With a food mill or food processor, do your mushing and then scrape the result into a saucepan. With a blender, add a little chicken broth to your vegetables and whiz away, and then pour into a saucepan. With a hand blender, you can puree right in the saucepan. In any case — and I hope this much is apparent — you’ll need a saucepan.

I’m not going to tell you how much liquid to use because the answer depends on a lot of variables, as well as your preference for soup thickness. But use chicken stock or broth. Heat your vegetable mush with the stock.

Now take a little piece of fresh ginger, maybe the size of Raymond Burr’s thumb, and peel it. If you have an oroshiki, which I do, use it to grate the ginger.

If you don’t have an oroshiki, then use a cheese grater. For a quart or so of soup you’ll need around a teaspoon of grated ginger, but this, like everything else in the recipe, is according to taste.

After the soup is hot, and the right thickness is achieved, and the ginger is added, you may adjust the seasoning, and it’s ready to serve. It is wonderful as is, but a nice touch of foof would be to put a little dollop of crème fraîche or sour cream in the middle of each serving, which you’d then scatter with chopped chives.

That’s my roasted carrot and ginger soup.

PS: It occurs to me just now that you could chill your soup, add cream to it, and end up with something lovely and salmon-colored.

TOMATO PIE

June 28, 2016

A couple of years ago I wrote a little about Laurie Colwin. I wrote about the way she wrote about food and cooking, about her gentle, unique manner of telling you how to do something without being pedantic. She wrote as if she were talking to you over coffee at the kitchen table, and she told you things that made you turn around, open your doodads drawer and get out a note pad and pencil so you could write everything down.

It was as I finished the first essay of hers I ever read — a piece in Gourmet magazine about lentils, sometime in the early ’90s — that I learned she had died. She died at 48, which, for my money, is far too young, though it does beg the question of when we should really not say things like “far too young” when discussing people’s deaths. If someone dies when she is 96, would we say she had died far too young? What if she were 14? What’s just young enough? Maybe it’s not a phrase to use at all.

Anyway, Laurie Colwin wrote some novels and short stories, none of which I’ve read. I’ve made up over the years, though, by reading many times her two…

It would be wrong to characterize Home Cooking and More Home Cooking* as mere cookbooks because they contain far more than recipes. More accurately they’re collections of essays, essays with recipes in them. More accurately still they’re stories about the way food fit into Laurie Colwin’s life as a child, college student and mom. The stories make you realize the ways food fits and might fit into your own life. At the end of each of these books you close it and hold it in your lap with a wistful expression on your face while thinking, “I want more!”

You can buy Laurie Colwin’s books here, and I urge you to do so. Here she is. Doesn’t she look like someone you’d want to have over for coffee?

What sparked this ramble was a plastic grocery sack full of tomatoes. When I arrived at work this morning there were a couple of them on a counter. They also contained a few bell peppers.

“What’s this about?” I asked the nearest person to where I was standing at the time.

“Usually when stuff’s there it means it’s for the taking.”

I asked around, found the donor-lady, and determined that it all was, indeed, for the taking. So I took. Three or four tomatoes seemed not excessive — those and a pepper — so I carried them home at lunch.

I also searched online and found Laurie Colwin’s recipe for Tomato Pie. I wanted to give the tomato lady something in return for her generosity and the recipe made good sense. Laurie Colwin’s Tomato Pie might just rank among the ten best things I have ever eaten, and the fact that I’ve made it myself enhances the satisfaction I’ve experienced over it.

Though I worry that it might render me a bad sport for reproducing the recipe here, when we all should pay for it, I shall take the liberty. Laurie Colwin’s Tomato Pie is that good. Here is her story:

I have never yet encountered tomatoes in any form unloved by me. Often at night I find myself ruminating about two previously mysterious tomato dishes, which I was brazen enough to get the recipes for. One is Tomato Pie and is a staple of a tea shop called Chaiwalla, owned by Mary O’Brien, in Salisbury, Connecticut. According to Mary, the original recipe was found in a cookbook put out by the nearby Hotchkiss School, but she has changed it sufficiently to claim it as her own.

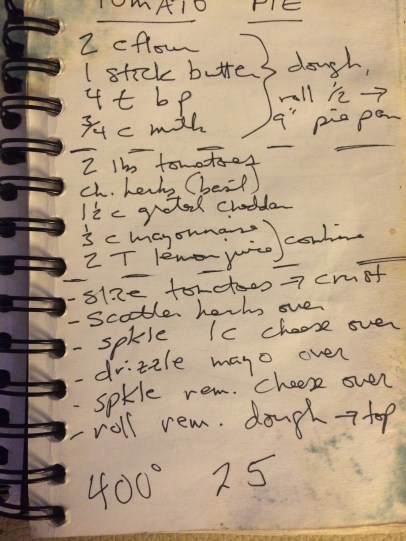

The pie has a double biscuit-dough crust, made by blending 2 cups flour, 1 stick butter, 4 teaspoons baking powder, and approximately 3/4 cup milk, either by hand or in a food processor. You roll out half the dough on a floured surface and line a 9-inch pie plate with it. Then you add the tomatoes. Mary makes this pie year round and uses first-quality canned tomatoes, but at this time of year 2 pounds peeled fresh tomatoes are fine, too. Drain well and slice thin two 28-ounce cans plum tomatoes, then lay the slices over the crust and scatter them with chopped basil, chives, or scallions, depending on their availability and your mood. Grate 1 1/2 cups sharp Cheddar and sprinkle 1 cup of it on top of the tomatoes. Then over this drizzle 1/3 cup mayonnaise that has been thinned with 2 tablespoons lemon juice, and top everything with the rest of the grated Cheddar.

Roll out the remaining dough, fit it over the filling, and pinch the edges of the dough together to seal them. Cut several steam vents in the top crust and bake the pie at 400F for about 25 minutes. The secret of this pie, according to Mary, is to reheat it before serving, which among other things ensures that the cheese is soft and gooey. She usually bakes it early in the morning, then reheats it in the evening in a 350F oven, until it is hot.

It is hard to describe how delicious this is, especially on a hot day with a glass of magnificent iced tea in a beautiful setting, but it would doubtless be just as scrumptious on a cold day in your warm kitchen with a cup of coffee.

By the end of today the grocery-bag bounty had diminished somewhat but many tomatoes and peppers remained. Not wanting my coworker to feel that her gift was unappreciated I took another pepper and several more tomatoes. By several I mean six. Maybe seven but a couple were small. Eight is a rounder number.

Laurie Colwin’s Tomato Pie is easy to make and it’s delicious but the bigger point is that you don’t have to fuss over it. I’ll prove that to you in a minute with my photo diary of the Tomato Pie I made this very evening.

I have my own cookbook, by the way. Since 1997, when I began cooking for a living, I have collected recipes of things I believed were in no need of improvement. Once I settled on basic ingredients and proportions thereof for, say, crème Anglaise, crème patissière, or pizza or biscuit dough, I entered those recipes in my book and stopped searching.

Here is the page in my book for Tomato Pie. Within my shorthand is a presumed understanding of technique, which I suppose comes from two years in culinary school, from which I graduated with high honors. (Notice the different annotations for teaspoons and tablespoons; that don’t come cheap.)

To begin, the tomatoes.

And you make the biscuit dough.

If, by the way, you aren’t comfortable making your own biscuit dough, the Tomato Pie recipe will work if you instead buy a can of refrigerated biscuits and flatten them out into a pie pan.

And if you do not have any fresh basil, you can put some dried basil into the mayonnaise-lemon juice mixture. That is what I did tonight. For that matter you can use oregano, tarragon, crushed red pepper, or any other seasoning you like, and things will end up swell. The mayonnaise and lemon, however, are pretty much essential.

Please notice that I did not fuss over the bottom pie crust. For one thing it was very hot outdoors and I was therefore in a grouchy mood. Beyond that, the front-room air conditioner is inadequate for cooling both the front room and the kitchen and I was wet around the neck.

Also notice that there are hardly 1 1/2 cups of grated cheddar cheese atop the tomatoes.

In our refrigerator there was only a Snickers bar-sized hunk of cheddar cheese. I grated that and used it here but I also added a handful of crumbled goat cheese. Improvisation, after all, is next to godliness. That and fiber.

The biscuit dough is not worth fretting about. Just roll it out between two sheets of waxed paper. Or press it into the pie pan with your fingers. However you do it just get it into the pan and over the tomatoes and bake the thing.

I already had dinner tonight. The tomato pie is for tomorrow. Because you read Laurie Colwin’s recipe you know that this dish works at least as well when reheated the next day.

I’ll likely forget to take pictures when I cut into this pie tomorrow.

UPDATE: What do you know? I remembered to take a picture.

*I loaned my copy of More Home Cooking to a then-friend a while back and never saw it again. I really need to replace it. He isn’t my friend anymore but I won’t explore here to what extent the situation is because he has my copy of More Home Cooking.

SUBSTITUTIONS FOR THINGS

August 23, 2015

Calvin made rice last week, in part because he has a touch with rice but also because I do not like making rice. The technique I learned in culinary school for making rice—on which I will not elaborate here because it bores me and this post is not about rice, except for the rice dish Calvin made last week—will wait for another day or forum to receive its moment under the spotlight.

We had no long-grain white rice in the house but the rice Calvin contributed to the dinner table was fluffy in spades, each grain lovely but distinct from its siblings, like Jolie-Pitt kiddies. I wondered where the rice came from so I asked him.

“Where did this rice come from?” I queried.

He explained that he used Thai sticky rice (Oryza sativa var. glutinosa), which is usually sticky, thus its name. I wondered why, this time, it was not sticky.

“Why, this time, is it not sticky?” I asked, and Calvin shared his technique with me. First he boiled the rice, as one might do when one is preparing, say, boiled rice. After that, he drained the rice in a colander and rinsed it under running water. Then he dumped the boiled, drained, rinsed rice into a bowl—a microwave-safe bowl, for reasons that will shortly become clear—and finally, just before the main course was ready, gave it a couple of minutes in the microwave. Perfection. Chef Péladeau, my Québecois instructor at the Cooking & Hospitality Institute of Chicago, urged us students to cook “wit’ love, always wit’ love,” and Calvin’s sticky rice adaptation betrayed a love of rice. I ate it happily.

Calvin made use of what he had. He made it work. He adapted techniques he knew to the ingredients at hand, reminding me of the value in cooking of the art of adaptation.

I wrote in these pages some months ago about options for dressing your mashed potatoes if you were out of milk and butter, or if perhaps you merely felt like a change. Chicken stock, sour cream and olive oil offer delicious alternatives to the traditional approach.

As a public service—I am nothing if not a servant of my public—I have prepared a list of ingredients that might be called for in recipes but which you might not have, along with my suggestions for substitutions.

- SYRUPS FOR BAKING—The intrepid cook will encounter recipes calling for corn syrup (light and dark), molasses, honey, and, if the intrepidity is extreme, Steen’s syrup from England, or possibly sorghum syrup from the American South. Alone or in combinations, these are usually interchangeable, with some adjustments for sweetness. For instance, most pecan pie recipes call for corn syrup, but in a pinch, or for the sake of variety, having eaten your Aunt Gloria’s workaday pecan pie with cardboard crust for four decades’ worth of Thanksgivings, you might try, as the teens say, mixing it up. Keep in mind that, in general, molasses is sweeter than corn syrup—honey is, too—so you’ll need less of it. In those cases you can add a little water to the substitute. If you Google “substitute corn syrup molasses honey” you will find more detailed information, or “info.” My role here is to point out that you can make substitutions, not to do all the work for you, the reader.

- WINE FOR COOKING—You can try putting beer in recipes instead of wine but you’ll do that at your own risk. (Again turn to Google, and look for Carbonnade à la Flamande, which means “Flemish Carbonnade.”) If you go the beer route and things turn out badly, don’t use my name. Chicken or beef stock is usually a safer alternative.

- CHICKEN OR BEEF STOCK—These are kitchen staples but if you don’t have any you can dress water up sufficiently to take to the ball. Simmer water with a carrot and half an onion, and celery if you have any, which I often don’t because while celery is useful in cooking I despise it raw and don’t like it near me. To the vegetable water toss in a few peppercorns and whatever herbs—fresh or dried—make sense to you. Do not use turnips here. Strain this tea and use it in recipes when you don’t have chicken or beef stock. But you really ought to have chicken or beef stock in the first place. Chicken, at least.

- BUTTER—Pretty much anything that can be fried or sautéed in butter can be fried or sautéed in oil. Meat, vegetables, eggs, bread for croutons, anything. In fact, eggs scrambled in olive oil are an exotic delight. Finally, I am talking here about butter in the frying pan, not butter in baking. It would be a mistake to put a cup of olive oil in your Devil’s Food cake batter.

Or you could just get in the car and drive to Piggly Wiggly.

It is worth mentioning that there are times when a substitution is simply a bad idea. If, for example, you wish to make bread but have no flour, the inadvisability of substituting cornstarch for flour in your recipe cannot be stressed enough. Likewise, do not use tofu when you have no meat or prefer not to eat meat. Tofu might have uses but as a meat substitute it is not, or should not be.

If a cocktail recipe calls for orange juice and you are out of it—if you never drink orange juice, “out of it” does not really apply, since “out of it” implies the regular presence, or “stock,” of something—do not substitute lemon juice for it, jigger-for-jigger.

In situations like this you are better off going out to eat, or to a bar.

A LESSON FROM CULINARY SCHOOL REGARDING ESPRESSO

August 1, 2015

No crema, no serva.

MY CHICKEN RECIPE

July 13, 2015

There is a thing I do with chickens, and because a considerable number of people have used complimentary terms when referring to this chicken-thing I decided to share it. (There is a case to be made that what I do is more a matter of doing it to chickens rather then with them since they are beyond having the ability to express an opinion; they participate only passively. On this point I will not be adamantine.)

Stand a whole chicken on its head-end on your cutting board. If it’s easier for you, imagine yourself holding a baby’s little ankles with one hand while you wipe his or her backside during diaper-changing time; that is generally what you’ll be doing with the chicken. Next, though, you should stop imagining that it is a baby in your hand because you’re about to remove its back and that’s not something you really want to do to a baby. They make so-called poultry shears for this operation but it’s easy with a chef’s knife if you keep your knives sharp. Just cut downward along each side of the backbone and you’ll end up with a beige thing about the size of a PayDay bar, along with, of course, a backless chicken. Put the back in a baggie and freeze it. You’ll make stock later, when you have enough chicken parts saved up.

Now spread the chicken out, his breast facing up, on your cutting board. Press the heel of one hand over him and lay your other hand atop, as if you were going to perform chest compressions during cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Lean over the cutting board and push down. Let your body, not your hands, do the work, and you will hear and feel the bird’s breastbone crack, rendering him more uniformly flat. You have now spatchcocked your chicken. You will get mileage in conversation at parties and your kids’ soccer games by referring casually to your having spatchcocked a chicken.

Place your chicken in a mixing bowl or a large plastic bag. To the bowl or bag add

a couple of tablespoons of olive oil,

a few big pinches of salt,

several turns of black pepper,

a few cloves of garlic, peeled and smushed, and

a lemon, cut in half. Squeeze the lemon halves as you toss them in with the chicken.

If you have fresh herbs around you may use parsley, basil, oregano, rosemary to whatever degree makes sense to you. Don’t bother chopping them. You could also include some red pepper flakes or all or part of a chili pepper. I am nobody’s idea of a snob about dried herbs but they’re no help in this recipe.

Once everything is in the bowl or bag with your chicken, you’re welcome to turn the bird over a time or two to get everything onto him but don’t fuss too much about it.

You can cook this chicken in a couple of ways, but in any case please allow at least two hours of soaking time. It helps. Just before cooking, remove the chicken from his bath – save the bathwater! – and dab him dry with paper towels.

If indoors, you’ll heat a large, heavy skillet on the stove. (You will already have turned on the oven and set it to 400 degrees.) Drizzle just a little oil into the hot pan. Plop your bird in, breast down, and leave it alone. Don’t poke, prod or fiddle. You may, however, jiggle the pan some if it makes you feel good.

After five minutes or so you can peek at the skin down there. Once it has acquired crispness and a brown shade that makes you think of the dashboard of the Mercedes your rich friend gave you a ride in once, you may turn the bird over. Use tongs here, and don’t fret if you tear the skin; stuff happens.

Open your oven door and put the skillet in that hot chamber. Place the two lemon halves on top of the chicken. Close the oven door. In 20 minutes, open it again and pour the marinade (you saved it, remember?) over the chicken. In ten minutes more, remove the pan from the oven.

Cut up the chicken and serve it.

You can also cook your bird outdoors – and this is my own preference because smoke makes most meats better, in my view – the only difference being that there’s an extra flip. Start him breast up on a hot grill, and then after about ten minutes turn him skin-to-grill. This is the only challenging part but it’s important because you still aim for brown skin and not black ash. Here you may prod and fiddle because it is important not to let your chicken’s skin carbonize.

When the skin on the breast has become an alluring mahogany shade it is time to make your final flip. Skin up, you’ll need another ten minutes…ish. A few minutes before you think the thing is done, drizzle the contents of your marinade bowl over the chicken.

(I thought briefly about including instruction on how to tell when chicken is cooked to a safe degree but decided against it. The subject bores me.)

Anyway, when the chicken is done, take it inside, cut it up, and serve it.

THINGS TO DO WITH MASHED POTATOES

December 27, 2014

People put milk and butter in their mashed potatoes because milk and butter make sense in mashed potatoes. Mashed potatoes taste good that way. But milk and butter are far from the only things you could be putting in your mashed potatoes.

Before we get into additions it is worth reminding you, or telling you if you didn’t already know, to give your potatoes a little time over heat before you add anything. After you’ve boiled them, drained them and mashed them, stir them for a minute or so over low heat. You’ll notice a cloud of steam rise from the pan and that’s good. That steam is water, which does your mashed potatoes no good at all. Getting rid of water in the potatoes is like applying primer to a wall before your color goes on. The potato will be more receptive to whatever it is you decide to do with it.

Here are some things you can put in mashed potatoes:

- Sour cream. You get your richness with a little bonus tang. If you’re worried about your figure you can use fat-free sour cream. This is one of the few times when fat-free sour cream is good for anything.

- Chicken broth. With or without butter, stock is a user-friendly alternative, even if it’s the cheap kind.

- Olive oil. You’ll still need some liquid but olive oil instead of butter gives your potato a swarthy, exotic flair.

- If you’re going the milk-and-butter route, try heating the milk beforehand with several cloves of garlic in it. The garlic will soften and the sharpness of its flavor will subside, so your potatoes will end up with little smooshes of garlic in them.

- Butter, bacon, chives, sour cream, cheese. If that stuff is good enough for baked potatoes, it’s good enough for mashed potatoes.

- Salad dressing. The creamy kind (ranch, blue cheese) works but so does vinaigrette.

Whether you find yourself without milk or butter or you just want some variety, give one of these ideas a try.

YOUR FRIEND, VINAIGRETTE

December 21, 2014

Vinaigrette is, depending on your perspective, a ridiculously simple salad dressing or a wildly exotic-sounding one. Put oil and vinegar together in a bowl and you have vinaigrette. Add some finely-chopped shallot or garlic and your vinaigrette gets better. Pinch in a little salt and grind in a little pepper and it’s better still. Mustard is an emulsifier, so if Vinaigrette Separation Anxiety torments you when you cook, include a half-teaspoon of the Dijon stuff, which keeps things cohesive and happens also to taste good. And herbs! Parsley, basil, tarragon, mint—fresh or dried—will all improve your vinaigrette.

You likely know that olive oil is the commonest oil to use to dress a salad but it’s hardly the only one. Walnut and hazelnut oil give a…well, a nutty sophistication to your vinaigrette. There’s also garlic oil but it’s a poor, lazy substitute for fresh garlic. (An amber clove of mushed-up roasted garlic sounds like a good idea, too, now that I think of it.)

If you’re getting all Asian-y with things you can use sesame oil but tread very lightly. It’s strong and a quarter-teaspoon will aromatize enough salad for eight people. Start with peanut oil or mild olive oil, then think of sesame as vermouth and your dressing as a martini. In certain precincts of Central and Eastern Europe they press the seeds of a particular variety of pumpkin to make oil from them. Kürbiskernöl in German, ulei de dovleac in Romanian, and other names in other languages, it is highly aromatic and intensely flavored. It is also an attractive deep green color and will not come out of your clothes if you drip it on them.

Oil isn’t the only vinaigrette component with which you can let loose. (I might have said let your hair down except that would be rather gross in a kitchen situation.) Depending on whimsy and what’s in your pantry there’s red wine vinegar*, white wine vinegar, cider vinegar, rice vinegar, balsamic vinegar, sherry vinegar—the list goes on.

For the purposes of vinaigrette, when we say vinegar we really mean something acidic, and acid comes in many forms. Lemon juice and olive oil make for a sprightly dress-up for summer arugula. Squeeze the juice from a tomato, add salt, pepper and fresh basil, then whisk in first-quality olive oil, and you have something to turn heads. You’ll see strawberry and raspberry vinaigrettes on restaurant menus but I haven’t been fond of those so will not endorse them here.

Beyond a delicate cloak for salad greens, vinaigrette waits to serve you in other dishes and uses. A marinade for meat is just translated, transmogrified vinaigrette. Acid, oil, seasoning: think of marinade like you now know to think of vinaigrette and you’re in good shape.

Finally, there is something I used to make a lot when I cooked in people’s homes for a living, and it always drew compliments. I will now tell you about it.

Boil or steam some rice (any color), then drain and rinse it to cool it down. Dump it in a big bowl. Boil some pearl barley, then drain and rinse it to cool it down. Dump it in the bowl with the rice. Scrape some corn kernels off some very fresh ears of corn, and dump the corn into the bowl you have going. You can also use—egad!—frozen corn that you have thawed, boiled or tossed in a very hot skillet to impart the tiniest bit of char. If you have and like lentils you can cook some of those, too, then add them to everything else. Chop some green onions (the green part and the white part—no need to be fussy about any of this) and throw them in with your other stuff. Now make a vinaigrette, any kind, and add it to your bowl of stuff just as you’d dress a salad. Taste as you go so you don’t end up with something too sour, too salty or too wet. Serve it at room temperature. This thing (I never made up a name for it) travels nicely, which makes it convenient to take on a picnic or cattle roundup.

I urge you to experiment with vinaigrette. Let it be your friend. It wants to be.

*Make your own red wine vinegar. The next time you have red wine, leave a tablespoon or so in the bottle. To that add a tablespoon or so of cheap wine vinegar, red or white. Cork the bottle. Every time you drink red wine, save a few drops for the vinegar. You don’t have to add more vinegar—just wine. After a bit you’ll have red wine vinegar far better than what you get at the store. My bottle began sometime in the mid 1980s and contains, among other things, drops of Lafite ’82. I can’t say that anyone tasting it would know there was Lafite ’82 in it unless I told them, but I like knowing it’s there. (Note: This system does not work with white wine vinegar. I’ll spare you the chemistry lesson but trust me here.)

MOST-USED KITCHEN IMPLEMENT (Non-cutlery)

December 20, 2014

Pie pans: old, beat-up pie pans. If you’re like me (good or bad, not many of you are but I thought it would be polite to suggest the possibility) you’ve brought a pie home from Marie Callender’s or bought a frozen one. (Ed. note: The frozen Dutch apple pie from Claim Jumper is one of the 10 best desserts I’ve ever eaten, this in a life involving many desserts.) You will be left with a flimsy pan with knife marks across the bottom.

This pan is ideal for keeping your meat near the stove top before cooking it. It’s also good for keeping the meat hot after you cook it (“let the meat rest before carving or serving” blah blah). And for schnitzel it’s hard to beat an array of pie pans for the flouring, egging and breading.

An additional benefit is that they are lighter than plates and other ceramic dishes, thereby causing you to exert yourself less when pulling them down from the cupboard or, once you’re finished with them, transporting them from the countertop to the dishwasher. That saved physical energy is, in my opinion, better directed toward whisking, flipping, or the hoisting of wine glasses.

Bonus tip: You will occasionally see pie pans that have little holes on the bottom, which some bakers believe helps with the browning of bottom crusts. My advice is not to put anything wet in these pans. Or anything powdery.

Bonus tip #2: You can also use pie pans for making pies.

FOOD TIP #253

December 15, 2014

“Fresh-squeezed orange juice is the best.” Depending on the oranges, yes. But if you have inexpensive orange juice from a carton, or even the frozen kind, there’s an easy way to spruce it up. A single drop of Angostura bitters will make the cheap stuff taste like fresh-squeezed. Try it!