Crowds of people are not my idea of a good time. I like my space and I don’t like noise.

Crowds of drunk people are especially troublesome. The evenings I spent in Chicago gay bars in the 1980s gave me my fill of noisy masses of drunk people. I’m good.

Despite my aversion to large gatherings of people — I allow exceptions in situations where I have a ticket granting me exclusive use of a seat in a theater, showroom or stadium — I have found myself over the years in more than my share of New Year’s Eve crowds. The televised time-zone-by-time-zone festivities two nights ago brought to mind some of the more memorable among them.

It might seem that, short of an English soccer stadium during a brawl, New Year’s Eves would present the worst possible conditions for crowd-enjoyment. Many people compress into small spaces, they usually swig gallons of alcohol in the hours before midnight, and at the stroke of 12 they yell. I do not care for crowds of drunk people, yelling.

And yet, over the years and in several states and countries, I have found myself amid some of those very crowds I profess to hate and still managed to have a good time.

Before the days of matrimonial attachment I had my own New Year’s Eve tradition. I prepared moules à la marinière, or mussels in wine, and drank bubbly. Champagne was beyond my budget so the wine was usually something sparkling from the Loire. I timed the meal so that I ate around 11, after which I took a bath. I rang in five or six new years in bathtubs, drinking Saumur. It was a good tradition.

Within a few years of said domestic attachment we lived in Chicago, where the city put on a fireworks show over the lake. My memory of those new years is vague but everything must have worked out because if it hadn’t, I’d remember. What goes wrong tends to stick with me.

Calvin’s and my first out-of-town New Year celebration was December 31, 1998, in Zurich. A clean and pleasant city any day of the week, on New Year’s Eve in Zurich everyone turns out downtown along the lake and the river. At midnight they shoot fireworks.

It’s common at street festivals to see stalls and portable shops where food and drink are sold. In Zurich on New Year’s Eve they offer Raclette and Champagne, both of which we bought and enjoyed very much while squeezed among the masses on the Münsterbrücke bridge. Taittinger by the bottle eases the stress of a crowd, even when drunk from plastic tulips.

The next year, for the arrival of the new millennium, Calvin and I did the so-called Times Square Thing. I was anxious about the prospect — I knew enough about New York to doubt that Raclette and Taittinger were likely to appear among street-food vending stations, and I wondered if the Times Square crowd would behave as civilly as the Swiss had the year before — but if I was going to jump into the pool, the deep end was as good a place as any. How bad could it be?

Strictly speaking, we were not in Times Square at midnight. After dinner at Cafe Luxembourg, on 70th Street near Broadway, where I ate salmon with lentils, we headed south. The sidewalks were full, and most of the people filling them were also heading south toward where the action would soon be.

But Broadway and 56th Street, still more than 10 blocks from Times Square, was as close as we came to the action. In each block the police had arranged corrals in the streets, formed with steel barricades, leaving space around the corrals for them to move around and to ensure that no one got out. Once a pen was full, the police directed people to a pen in the next block. The system kept order.

We were ten or so blocks from the action when the ball dropped but close enough to see a sliver of bright light squeezing from between the buildings on either side of Broadway.

People behaved themselves, and by five minutes past midnight the authorities released us from captivity and the crowd dispersed calmly. Dick Clark was still alive then but we didn’t see him.

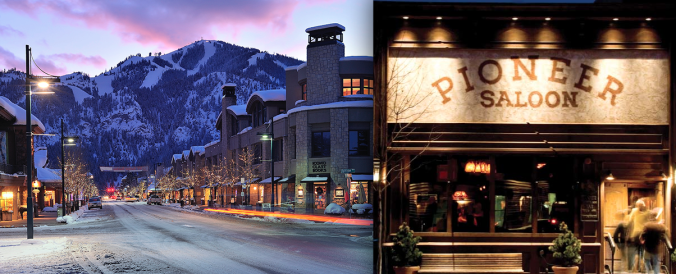

We spent the next six new years improbably in Ketchum, Idaho, where the family I by then worked for also spent their holidays. That family always went out for New Year’s Eve, giving me the evening off, and Calvin and I settled into a routine involving dinner at the Pioneer Saloon.

A steakhouse with Old West decor and a menu ranging not far from beef and baked potatoes, the Pioneer was packed on New Year’s Eve, even more so than the corrals on Broadway. But because most of their business was groups larger than two people, the two of us rarely had to wait as much as an hour for a table.

Those were fun dinners, and as often as not we sat at the Pioneer, working through steak and Cabernet, when midnight came.

Only once in Idaho did we not go to Pioneer Saloon. That year I was hired to make dinner for two families who were sharing a large house they had rented for the holidays. Calvin went along and helped. The client wanted steak so steak I gave them. It required firing up the gas grill on the rear deck, so I was in and out of the kitchen, scarved and gloved up because it was snowing heavily, making for one of my more memorable cheffing jobs.

At midnight the clients invited Calvin and me to join them for their toast. We would have accepted even if it weren’t Dom Pérignon they were toasting with, but Dom Pérignon made the toast better.

I really shouldn’t name the people who hired Calvin and me that New Year’s Eve because I don’t know how sensitive the Rob Lowes and the Kenny Gs would be about such things.

After Idaho there were a couple of Palm Springs new years and a few at home. Also maybe one in San Francisco but I’m not sure. When 2012 arrived we were in San Diego, in a Hillcrest bar. The bar part wasn’t memorable but by 1 a.m. we were in the Crest Cafe, where I ate a memorable slab of chicken.

East Texas Fried Chicken, they called it. For that matter, they still do. I can’t imagine a reason to change the name of a good plate of food. The buttermilk batter served not only to give a tangy, crunchy cloak to the chicken but also as a vehicle to hold a big handful of jalapeño slices in place. There may come a day when food like that will keep me awake, but on January 1, 2012, it didn’t.

A year later we were back in Zurich. Before joining the crowd along the lake we ate dinner with our friend Anna at Kronenhalle, a grand and amusingly stuffy restaurant where they prohibit photography, even of your own food. Because the schnitzel was good, I rebelled. Anna was not pleased with me.

Just as before, the Swiss people behaved themselves. At midnight, everyone turned to the lake, awaiting the fireworks. We waited and we waited.

“This is strange,” Anna, who is Swiss, said. “Where is the feuerwerk?”

Her apparent confusion over something Swiss not working the way it was supposed to drove her temporarily to her native language.

“I really don’t understand this,” she said.

Around 10 minutes past midnight a few flashes appeared in the sky but they didn’t look much like the pictures in the tourism brochures. The flashes we saw over Zürichsee seemed more fitting for a Fourth of July celebration in one of the more impoverished Appalachian towns.

“Well, that’s not really very good,” Anna said with dismay when the flashes ceased a minute later. We looked at each other.

Not wishing to appear disapproving in a place where we were mere visitors, Calvin and I smiled meekly.

“I guess we can leave,” Anna said disappointedly, to which we agreed. On the walk to the train station — Anna lived in the suburbs — we noticed an interesting car.

We had been on the tram only for a minute or two when the sky lit up over the tops of buildings. The sky exploded, really, in the direction from which we had just come. Anna looked at her watch.

“It’s late,” she commented. Swiss timing didn’t work so well that night. (We learned later that the fireworks authorities wait until the church bells stop their midnight ringing before igniting everything. It seemed a gentle courtesy.)

A year later we were in Paris. The Eiffel Tower is the center of attention on New Year’s Eve so that was where we planned to be at midnight.

We ate dinner at Brasserie Balzar, a bourgeois but unstuffy place in Saint-Germain-des-Près. We sat next to a couple with a 12- or 13-year-old boy. The child had a glass of Champagne with his dinner and seemed far less beguiled at the situation than we were.

The evening was cold but pleasantly so, so we decided after dinner to walk the two miles to the Eiffel Tower. The closer we came, the more crowded the sidewalks.

We popped into a wine shop and bought Champagne for midnight. They’ll give you plastic cups in Paris when you buy a bottle of wine for un pique-nique or other outdoor imbibing.

As in Zurich, people behaved. We stationed ourselves at the eastern end of the Champ de Mars, where folks were not compressed too much but where our view of the tower was unobstructed.

The light show at midnight was for the ages. The tower seemed to electrify from bottom to top, spraying beams of light up and out. At 15 or 20 minutes past midnight, when the lights dimmed, people began to drift away. It was a fine way to begin 2014.

Two nights ago we welcomed the new year in our little house in Mississippi, where I took my first crack at seafood gumbo. It’s a religion around here and I wanted to do it justice.

The stock was homemade, made from shrimp shells and scrawny crabs they conveniently call gumbo crabs. As midnight approached and I stood over the stove, stirring roux, I began to fade. Instead of stirring until the goo in the pan was the color of a Hershey bar, which many advise for the best gumbo, I threw in the towel when the roux reached the shade of Dunkin Donuts coffee with two little things of half-and-half in it.

I nailed the flavor, if I do say so, though I wish I’d made more roux and the gumbo were thicker. But the sweet Gulf shrimp and lump crabmeat made up.

Last night I made a new batch of roux, this time starting well before 10 p.m., and waited with it until it finished its journey to Hershey. Into the gumbo it went, et voilà! Success.

New Year’s Eve, I suppose, can be a lot of things. On the whole I still detest crowds, but I don’t mind them very much in Paris. Or with Calvin.