My friend Rob, whose sharp eye and opinion I respect, put something on Facebook the other day about the kitchens of someone called Nancy Meyers.

Who is Nancy Meyers? I wondered, and why would her kitchens matter to anyone?

A Google moment later I realized that she is a filmmaker of some renown. I have viewed some of her movies, including Private Benjamin, Baby Boom, Father of the Bride, The Intern and…

In fact those are the only Nancy Meyers movies I have seen but I am aware of Protocol, What Women Want, and I Love Trouble.

Not identifying Ms. Meyers as a formulator of these movies I had never put it together that several of them involved kitchens in supporting roles.

If my friend Rob had written about Stanley Kubrick, David Lean, Sidney Lumet, Ingmar Bergman or Blake Edwards (pre-Blind Date, after which his muse was out to lunch) I might have spouted chapter and verse, but about this Meyers my knowledge was limited.

Indeed, it turned out that certain scenes in her films have taken place in residential kitchens, and I suppose those kitchens are attractive in their respective haut-bourgeois ways.

Is it a coincidence, by the way, that Ms. Meyers cast Diane Keaton in so many of her films? That’s a question for another time.

But Rob’s Facebook post made me think about other movie kitchens, and off the top of my head I remembered only a handful of them. They’re all interesting to look at but I wouldn’t necessarily want to cook in these kitchens or live in homes containing them.

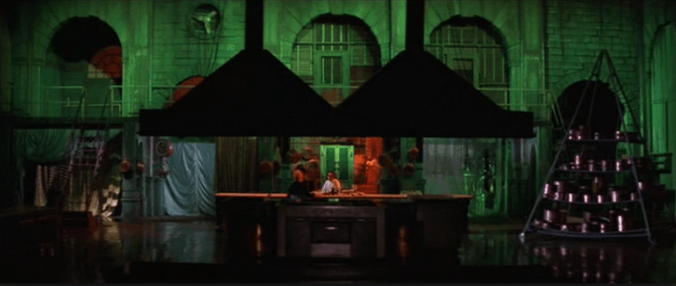

The kitchen in Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989) was a downer as kitchens go, and not one in which I’d much want to spend any time. For one thing — and this is a big deal when you’re cutting and sautéing things — it was dark. Even when you wield sharp knives of high quality it’s good to have bright light over your head, and Greenaway’s Cook/Thief/Wife/Lover kitchen did not have good light.

And the copper! After a certain point in life — I can’t define what that point is but whatever it is I’m past it — copper pots become a matter of more trouble than they’re worth. As a Christmas gift sometime during Bill Clinton’s first term my mother gave me a very pretty copper mixing bowl. Copper induces a certain chemical reaction with egg whites that nudges them into quicker, firmer peaks. I used the bowl when I made meringue or had other reasons to beat egg whites into peaks, and yes, it did its job.

But it smudged if you looked at it and it bugged me like crazy. No, thanks.

And I’m not even getting into the things The Cook cooked in The Thief’s kitchen. No, thanks.

The kitchen in Big Night (1996) was a restaurant kitchen. I could live with a restaurant kitchen, depending on the restaurant.

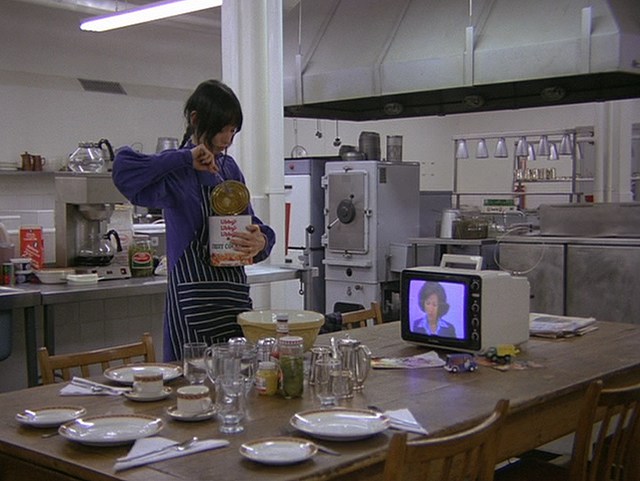

It would not, however, appeal to me to live with the kitchen in The Shining (1980). Not much. It’s too big and impersonal. An abundance of pans and bowls would be nice but I would not care for a ladder to be in my kitchen.

On the other hand, there is something to be said for a kitchen with a TV in it. TV figures prominently in my early food memories. It still does, truth be told.

I cooked three meals in this kitchen.

It belonged to an aging television tycoon who wandered in a couple of times while wearing a bathrobe and smoking a pipe. He was a Texan, which could explain his compliment after one dinner: “Clay, that’s the best steak I ever had in my life.”

When I asked the butler, however, what the tycoon would have said if he’d not liked my steak, the butler said, “He’d say, ‘Clay, that’s the best steak I ever had in my life.'” But I liked to look on the bright side.

The tycoon’s wife was not so benign. She and I, as they say, got into it over Romaine lettuce for the Caesar salad. I had not trimmed each leaf closely enough to the stalk for her taste. She had trouble describing what she wanted beyond, “I want it, you know, like restaurants make it.”

But after considerable discussion it turned out that she wanted there to be nothing green at all remaining on any lettuce leaf. She wanted Romaine stalks trimmed to within an inch of their lettuce lives so that they resembled spears of white asparagus.

“Like in restaurants,” she said.

The butler, who had tended to the mother of a certain British monarch before moving to Holmby Hills to tend to the TV tycoon, said he was sure he was followed by security operatives on his days off. He was sure his on-site apartment on the tycoon’s estate was rifled through by the tycoon’s wife when he was out.

The butler’s story provided some valuable context as I tried to make sense of the Caesar salad situation. The wife was a nightmare.

At the opposite end of the cinema-kitchen scale from The Shining is the tiny space in Robert Benton’s* Kramer vs. Kramer.

I’ve lived in apartments with kitchens like this — little linoleum-lined galleys. They aren’t the worst thing but I like room to move around when I cook. I also tend to use a lot of pans. Space is key, though not necessarily space for other people. I’m happy not to have company in the kitchen when I cook.

Now here’s a kitchen where I could have some fun. Babette had fun in it while preparing her eponymous feast (1987). Room to spread out, a hot fire, a nice table. Eat-in is fine as long as people aren’t under foot or — Lord no! — trying to help. (Help with opening wine bottles is allowed.)

I’ve heard that a particular challenge for actors is knowing what to do with their hands. This makes sense to me because most of us move our hands when we talk, some of us more than others, but it’s an irregular kind of movement. And in movies a particular action must be repeated many times so a scene can be photographed from different angles.

Brad Pitt seems to have found his answer to the hands question in food. That man eats more onscreen than anyone since Mr. Creosote.

It makes sense that so much movie action takes place in kitchens, since cooking and eating involve the hands.

The Castorini family’s kitchen in Moonstruck (1987) is a fine kitchen. Storage galore and that big table suitable for casual dining, breeze-shooting and pasta-rolling.

Ronny Cammareri’s kitchen in the same movie is not one of my favorites, though I’m hard pressed to say why. It’s clean, which isn’t a bad thing. Maybe it’s the stove. Maybe it’s the awful table and chairs. Then again, it could very well be that the kitchen’s perfectly fine and I’m turned off only because of the presence of Nicolas Cage in it. Nicolas Cage has never done it for me. He displayed a certain charm in Peggy Sue Got Married (1986) but after that, nothing.

My inclination toward things French is no secret, so the Arpel family’s kitchen in Mon Oncle (1958) has that built-in advantage. There isn’t much room to store things and I’d have to learn how everything worked, but I love the big window. I could live with that kitchen.

This list is hardly exhaustive but I suppose it must be significant because these are the kitchens that came to mind first. That’s how a shrink would see it, anyway.

And it struck me in making this list that kitchens don’t figure in the movies of the directors I most admire. Maybe Kubrick, Lumet, Bergman, et al., did a better job of giving their actors things to do with their hands.

*Robert Benton is someone I wish I could have known. For one thing, he was born and grew up in Waxahachie, Texas, which is where my mom’s mom was born and grew up.

For another thing, Benton had the presence of mind to hire one of my heroes in life, a cinematographer named Nestor Almendros, whose work inspired me and illuminated me. Almendros photographed Robert Benton’s Places in the Heart. He also photographed and won an Academy Award for Terence Malick’s Days of Heaven. He shot movies for François Truffaut (The Man Who Loved Women, The Wild Child, The Story of Adele H, The Last Metro) and Eric Rohmer (Pauline at the Beach, Claire’s Knee, Chloe in the Afternoon). He shot Sophie’s Choice, The Blue Lagoon and Koko: A Talking Gorilla.