In an earlier installment I made a list of the 10 most influential books in my life. It wasn’t easy to do, writing that list, but a friend had asked me to so I did. In my case, influence meant shaping a life philosophy, inspiring to write, learning what funny is. It was a tough but valuable exercise.

But books are hardly my only literary influence. Yesterday I learned that Stan Cornyn had died, not yesterday but almost two years ago. It jarred me a little.

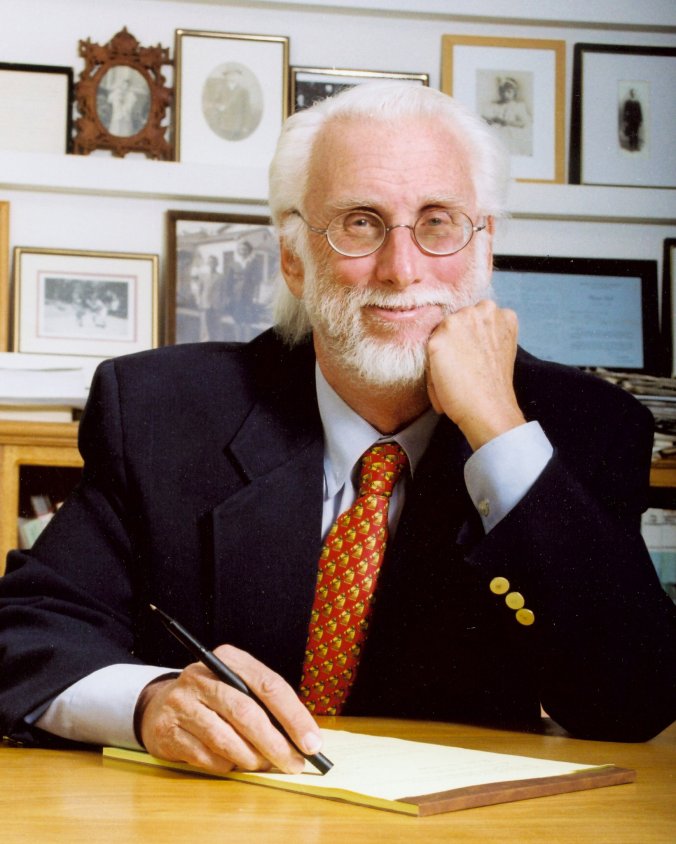

Stan Cornyn was a Warner Bros. Records marketing executive from the late 1950s through the 80s. His obituaries described him as “legendary” and “King of the liner notes.”

Mr. Cornyn won Grammy awards for writing the liner notes for Frank Sinatra’s September of My Years (1966) and Sinatra at the Sands (1967). He didn’t win the Grammy but was nominated for Francis A. & Edward K. (1969) and Francis Albert Sinatra & Antonio Carlos Jobim (1968) and Ol’ Blue Eyes is Back (1974).

I was well aware before yesterday of the distinctive quality of the words appearing on Sinatra album sleeves. Starting around age 13, when I began to purchase those records with my very own money, I read and reread the notes as I listened to the music, with no less reverence than girls of my age emblazoned pictures of Donny Osmond or David Cassidy into their heads. With time the cardboard words merged with the vinyl music.

It would not be an overstatement to say that Stan Cornyn helped shape my appreciation for descriptive prose as much as anyone else. I immodestly say now, as I reread Cornyn’s best work, that I recognize a tone that sometimes is my own.

September of My Years

Unruly fiddle players, who love recording like they love traffic jams, tonight they bring along the wives, who wait to one side in black beaded sweaters.

Sinatra begins to sing his September’s reflections. Jenkins, on the podium two feet above, turns from his orchestra to face his singer. He beams down attentively, his face that of a father after his son’s first no-hitter.

The wives in their black beaded sweaters muffle their charm bracelets.

A thousand days hath September.

Sinatra: A Man and His Music

Sinatra is fifty. But when he walks into a room — or into a world — there is no doubting where the focus is. It is on that singular man. On that man who stands straight on earth, sure in a universe rich with doubt. On that man, no taller than most, who came and saw and conquered.

Sinatra at the Sands

The house lights make us disappear and a stage comes alive. A professionally you-asked-for-it voice booms out, “And now …” and onto the stage comes a solidly built, short and seldom-smiling man. So short and squat it looks as if some monster thumb had been pressing him down toward the earth, gravity at last having done its dirtiest.

But Basie fights back, with the aid of a carefully selected crew and the kind of rhythm section your mother used to call “solid!”

Strangers in the Night

Animals may come, and they sure do go, but Sinatra stayeth. He stays to sing. Whatever it says at the top of your calendar, that’s what Sinatra sings like: 66. 67, 99 … He isn’t with the times. More than any other singer, he is the times.

If the electric guitar were disinvented tonight, a few thousand singers would be out on their amps. But not Sinatra.

That’s Life

Three days after the song created havoc in maybe a million Motorolas, Mr. Sinatra’s attention was drawn to the fact that he had done it once again: he switched his Vegas show so that “That’s Life” is now the closer. Mr. Sinatra could close with “Plucky Charlie Lindberg” and wrap up an audience good. When he does it with “That’s Life,” it’s a reasonable size war.

Other than that, not much else is happening.

Moonlight Sinatra

The Ring-A-Ding Kid steps away from the blare, the gears, the rock, the jazz, the noise. Leaves behind the sassy sayings, the flashy fun-fun. Escapes the stale smoke of yesterday’s disappointment.

Steps out into timeless new night air that snaps at the face, felt. It is a quiet world he steps into: intimate as two alone, soft as two together. Where the only clock that ticks is Life’s. Where the only sound is the sound of thoughts that are honest, unborrowed. In that setting, refreshing as young love, the stars come twice closer to eye, approach nearer to hand. The romantic mise en scene, Mendelssohnian in its aluminum newness, closes in around him.

Francis Albert Sinatra & Antonio Carlos Jobim

On the next number Jobim will sing duet with Sinatra. “Tone,” as Sinatra calls him, bends in close to his microphone. His hair undressed, finger combed. His jaw moving with precision, moving to each new vowel, his lips moving like yours do when you write a check for over $1000.

During playback, Sinatra leans on the conductor’s vacant podium. The only parts of him you see just popped white cuffs and worry lines in his brow. He’s Worry personified, like he’s in the last reel of “The Greatest Birth Ever Given.”

Around him circle the rest. The circle, too, listens to the playback.

Grown men do not cry. They instead put on faces gauged to be intent. They too listen hard, as if half way through someone whispers buried treasure clues.

It’s over. Sinatra walks away. “Next tune,” he says.

Around him, the circle. Half-stammering, half-silent, because they can’t think up a phrase of praise that’s truly the topper.

Except for Jobim.

He walks up to Sinatra. A peculiar walk, like he’s got gum on one sole. He puts his arm around Sinatra. He hugs Sinatra. Both men smile. Jobim turns out to look at the circle around them. His face alight, proud of his singer. His face triumphant. As if to say, and all along, you thought he was Italian.

Francis A. & Edward K.

A birthday event, hosted by Francis and Edward, you go to with your shoes high polished. Visitors who begin wandering in, high polished, are confounded.

First by Duke. Strolling through the door, six feet plus, dressed with wry urbanity. His blue sox rolled down to an inch above the ankle, and zoot! three inch cuffs on his slacks. Ellington moves across the studio floor to his permanent address: a pock-marked product of Steinway & Sons, once proud, now circle-scarred from years of forgotten coffee cups.

My Way

And if you hear of a man who will do it only his way — damn to high damn what other ways others expect from him — only ‘my way’ — then, that man is Frank Sinatra.

Ol’ Blue Eyes is Back

Inside Goldwyn Studios, a scuffy demi-movielot that looks like it’s hung around town only because nobody has come up with enough cash to level it and put up a good modern Zody’s in its place, there remains good Sound Stage Seven. Thirty feet up inside before you hit anything. Industrial walls. Its best feature is the “Fire Hose” sign.

String men, violins and violas, who don’t get called in to record as they once did, string men standing around the speakers now, listening, when a couple of years back they were out in the hall phoning their service.

“Gravity at last having done its dirtiest…”

Would you believe that I could have recited that line by heart an hour ago or a decade or two ago? Whether you believe it or not, it’s true. I know Stan Cornyn’s work.

Is there a big dose of hyperbole in it? Of course there is. The man was paid to sell records, after all.

For all the sassy sayings and the flashy fun-fun, the bottom line was, well…the bottom line. I came late to the record-buying world, but whatever it was that worked on me — the excitement of new music, the unidentified and unexplored pleasure of new ways with words — it apparently worked on other folks, too.

And although I have written gratefully few checks for over $1000, when I have, I have been aware of my lips moving like Jobim’s did when he sang with Sinatra.