Fifty years ago today, Frank Sinatra stepped into Studio 1 at Western Recorders in Hollywood. The building isn’t called that anymore—it’s still a recording studio, though the interior has been refitted by Philippe Starck—but it still sits at Sunset Boulevard and North Gordon Street, next door to Technicolor’s Los Angeles office and across the street from the Hollywood Palms Inn & Suites ($115/night at Christmas 2019 on Hotels.com).

Sinatra had been in Studio 1 before. He recorded “My Way,” “That’s Life” and “Strangers in the Night” there. He recorded his phenomenal 1967 album Francis Albert Sinatra & Antonio Carlos Jobim there. The themes from Mission Impossible, M.A.S.H. and The Godfather were laid down in the same 42’-by-58’ space as the music from Bullitt, Frosty the Snowman and Santa Claus is Coming to Town.

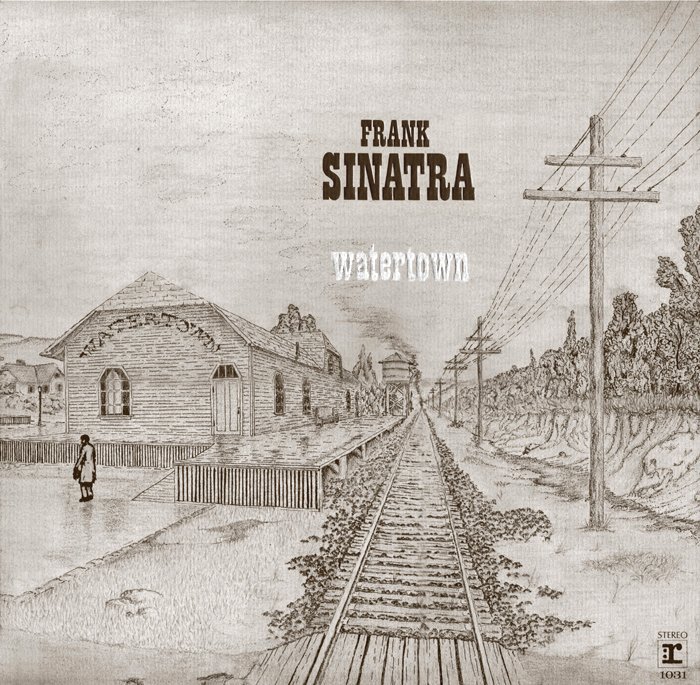

The session on November 7th wasn’t for an album; it was just for a song. Sinatra had recorded “Lady Day” barely a week earlier for his Watertown album. Watertown was a concept piece about a man whose wife has left him and their two young sons.

Watertown was the work of Bob Gaudio and Jake Holmes; they brought it to Sinatra fully realized. Gaudio, a member of Frankie Valli’s Four Seasons, had composed “Big Girls Don’t Cry,” “Walk Like a Man” and “Can’t Take My Eyes Off of You.” Holmes would later write jingles, including “Be a Pepper” for Dr. Pepper and “Be All That You Can Be” for the U.S. Army.

Watertown was complete by the end of October and ready for its eventual March 1970 release, but it didn’t include “Lady Day,” which was originally conceived as an epilogue to the album. The original recording was the first and last record for which Sinatra recorded his vocals without a live orchestra. But he returned to the studio to re-record the song—this time with the orchestra—as a single. It would be released that way in 1970, and a year later on Sinatra & Company, this time billed as a tribute to “Lady Day” Billie Holiday.

The November 7th session included musicians who had accompanied Sinatra before and who would accompany him far into the future. There was Irv Cottler on drums. Cottler was a sometime Wrecking Crew member who recorded with Nat King Cole and Ella Fitzgerald, in addition to touring with Sinatra for three decades. Sinatra called him “the best in the business.”

There was Bill Miller on piano; he worked with Sinatra for forty years. It was his plaintive accompaniment that set the scene for Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer’s “One for My Baby,” which Sinatra recorded first in 1958 for his Only the Lonely album.

There was Al Viola on guitar. He played with Sinatra for a quarter century in the studio and on the road. And he would work in Studio 1 several years after the “Lady Day” date with Sinatra, playing mandolin on the soundtrack to The Godfather.

A notable if incongruous member of the November 7th session was jazz guitar virtuoso Joe Pass—a true legend.

Jake Holmes, the lyricist, explained “Lady Day,” as written for Watertown, this way:

I saw the woman as someone who had talent. She wanted to be an artist or a singer. He was a hometown person. His whole orientation was family and business. He was the kind of guy who really lived in Watertown. She was more restless – a more contemporary woman. She wanted to do other things. She wasn’t liberated enough to tell him, and she didn’t think he’d understand. He was basically a good guy, but she wanted more. She abandoned her family and went for a career. The postscript was whether or not she got it and was it worth it.

Whatever the setting or motivation, the gravel in Sinatra’s voice in “Lady Day” suited the song. At age 53, he could not for much longer occupy the role of forlorn husband and father of young children.

Here is “Lady Day,” recorded November 7, 1969.