(NOTE: Today’s lesson is of the multimedia variety. Open another browser tab with this link and turn up the volume. And keep in mind that when you’re watching a YouTube video, you can pause and play by tapping the space bar. The time notations I use refer to the video to which I’ve linked.)

(UPDATE, October 7, 2014: The linked video no longer appears on YouTube because of a copyright claim by Sinatra Enterprises. This situation will hinder casual viewing but the program is still available for purchase via the link at the end of this essay.)

(UPDATE, November 5, 2016: I found the entire program online, courtesy of Instituto Antonio Carlos Jobim. The time markers in my essay will be a few seconds off but you’ll figure it out.)

(UPDATE, Oct. 2, 2017: The links seem to be dying around me. But I see that used DVDs are available for little more than a buck, so go ahead and buy the damn thing.)

There is no better embodiment of 20th century American popular music than the 52 minutes of recorded television called “A Man and His Music + Ella + Jobim.”

The man, of course, is Frank Sinatra, and the program, recorded over three days in October 1967, was his third “Man and His Music” special in as many years.

Sinatra was a busy man. Only a week earlier, on September 23, he and his children, along with Dean Martin and his family, taped “Christmas with the Martins and the Sinatras.”

And two weeks before singing “A Marshmallow World” on a Burbank soundstage on a warm afternoon with his Rat Pack friend Dino, Frank Sinatra engaged in a fistfight with a casino executive in Las Vegas, losing a front tooth in the struggle. The fight occurred during a two-week engagement of headlining performances at the Sands.

And just a few weeks hence his separation from Mia Farrow would be revealed in the press, only 16 months after their wedding.

Here was a man who did not seem to understand the concept of allowing his personal life to affect his work. Then again, for one of the most famous figures of his age, it would have been fair to ask what was the frontier between his public and private lives.

THE PLACE

NBC’s Burbank studios were just a dozen years old. The first television studios built exclusively for color broadcasting, they bore the name “NBC Color City.”

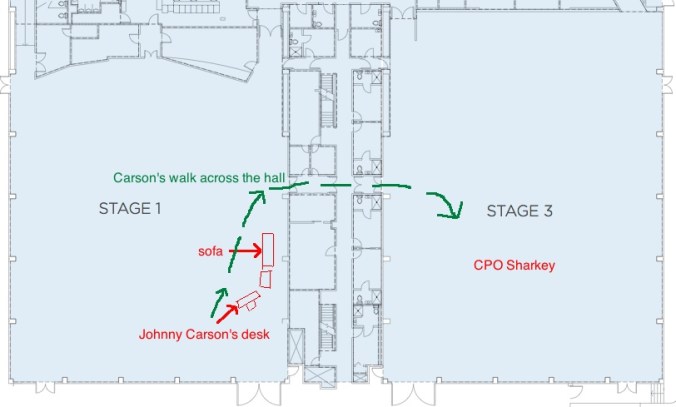

In 1972, when Johnny Carson moved The Tonight Show to California from New York, he took up residence on Stage 1. 30 years later, Jay Leno relocated across the hall to Stage 3, where he could be closer to the audience. Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In had originated from Stage 3, just as Bob Hope’s specials did.

Tonight Show fans might remember the time that Johnny Carson, returning from a vacation, discovered that his cigarette box had been broken by Don Rickles, the previous night’s guest host. An angry Carson, realizing that Rickles’ show CPO Sharkey was taping across the hall, left his own studio, walked across the hall with a microphone, and barged in on Rickles’ taping.

But I digress.

I have spent many hours researching this specific point, trying to determine the exact location of the taping of Frank Sinatra’s 1967 TV special. It’s clear that the first “Man and His Music” in 1965 originated from Stage 1 but details on the 1967 edition are considerably less accessible. I asked a friend who worked for the Jay Leno-era Tonight Show to put me in touch with appropriate NBC folks who might poke into the archives – and my friend obliged – but the well was dry.

It would make the story richer if I could point with authority to a square on a map and say, “THAT is where Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald and Antonio Carlos Jobim made great music in October, 1967.” Monuments are erected and battlefields preserved because they enhance the memory and remind us of the importance of historic events.

But here it will have to suffice to know only within a few hundred feet where this particular bit of musical history took place. Definitely, however, it was in Stage 1, 2, 3 or 4.

To reach NBC from his home at 100 Delfern Drive in the Holmby Hills neighborhood of Los Angeles, Frank Sinatra likely took Sunset Boulevard to Coldwater Canyon, turned left, followed Coldwater over the Hollywood Hills to the Ventura Freeway, then drove a few miles east to the Alameda Boulevard exit. There was NBC.

THE TIME

When Frank Sinatra woke up on Sunday, the first day of October, he saw in his newspaper that a Gallup poll showed Robert F. Kennedy ahead of President Johnson among possible candidates for the Democratic presidential nomination the following year.

The Chosen by Chaim Potok led the New York Times bestseller list.

Sinatra read about the previous evening’s 0-5 shellacking of the Dodgers by the New York Mets. (That very afternoon, however, the Dodgers would come back to beat the Mets at Dodger Stadium, 2-1.)

He might listen that afternoon to Dick Enberg announce the Los Angeles-Dallas game in the Cotton Bowl on KMPC radio (AM 710). The Rams pounded the Cowboys 35-13.

If he were at home that Sunday evening he might have watched a CBS News Special Report entitled “The Ordeal of Con Thien,” hosted by Mike Wallace. But he wasn’t at home that Sunday evening because he was in Burbank, taping his TV special.

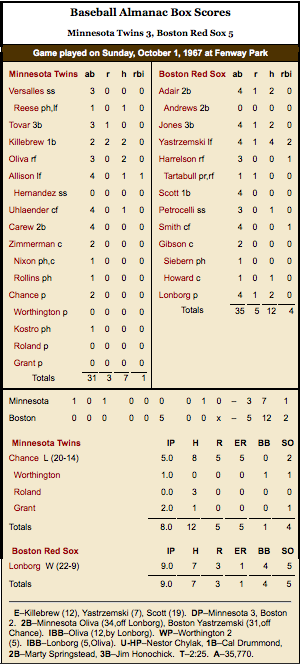

In the news of October 1st and 2nd, Sinatra would have heard about the Boston Red Sox capping their “Impossible Dream” season with victories over the Minnesota Twins that sent them to the World Series.

And on the morning of October 3rd, he would have read that Thurgood Marshall was sworn in the day before as America’s first black Supreme Court justice. This, by the way, was the only day there would be an audience in the studio at NBC, for the show’s final duet with Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald. I like to think that the news from Washington helped Ms. Fitzgerald and Mr. Sinatra to sing with a particular buoyancy that evening.

It was warm those first few days of October in 1967. Afternoon temperatures were in the low 80s.

THE SHOW

You will meet people who consider Frank Sinatra’s voice of the 1940s to be his best, most musical voice. Indeed, the voice of Harry James’ and Tommy Dorsey’s boy singer was satin. The voice of Anchors Aweigh and the MGM musicals – Till the Clouds Roll By, It Happened in Brooklyn, Take Me Out to the Ball Game and On the Town – was pure and soft. The skinny singer from Hoboken – known then as The Voice – simply stood behind a microphone stand and sang. On film he was likable and vulnerable.

Here is a clip from 1943’s Higher and Higher with Sinatra singing “I Couldn’t Sleep a Wink Last Night,” written by Harold Adamson and Jimmy McHugh. The song earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Song, but it lost to “Swinging on a Star” from Going My Way. Lyricist Adamson, by the way, also wrote the words to the theme from I Love Lucy.

You will meet other people who vigorously assert that the 1950s – the so-called Capitol Years – was the decade that set Frank Sinatra apart, that elevated him to a different pantheon. Specifically, his work with arrangers Nelson Riddle and Gordon Jenkins set a standard that has rarely been equaled and never been surpassed. Considering the entire picture – music, arrangements, voice, plus the introduction of the long-playing record – the 50s absolutely rank high in the history of Sinatra music.

Listen here to what many aficionados consider to be Frank Sinatra’s best recording ever. It’s Cole Porter’s song with Nelson Riddle’s arrangement, recorded close to midnight on January 12, 1956, at KHJ Studio A at 5155 Melrose Avenue in Hollywood. What we hear today was the 23rd take and it is a great recording but I do not think this was Sinatra’s best singing.

By the mid-1960s Frank Sinatra’s voice had deepened. It and he had matured. Having separated from Capitol Records and formed his own label a few years earlier, he spent more time performing in Las Vegas and making records he wanted to make.

In the early years of Reprise Records, Sinatra toured and recorded with Count Basie (along with Basie’s young arranger/conductor Quincy Jones) and he continued to make records with Nelson Riddle. He released his first live album, Sinatra at the Sands. A few months before those October evenings in 1967, he had won several Grammy awards: Record of the Year and Best Male Vocal Performance for “Strangers in the Night,” and Album of the Year for “A Man and His Music.”

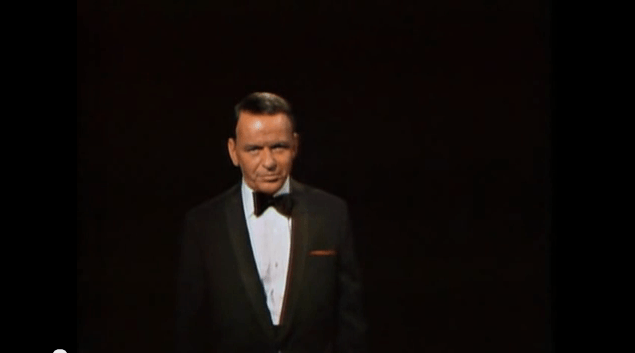

Frank Sinatra stepped onto that soundstage in Burbank, California, firmly in his middle age, two months shy of his 52nd birthday, yet on his NBC special he displayed his characteristic swing and swagger. Just look at the way his tuxedo-clad hips jut sideways in “Day In, Day Out.” (2:50) He looks like someone a third his age doing the Frug.

There is nothing wrong with this television program.

Some viewers might quarrel with the silly jokes and canned laughter after the first song (3:40). It’s a small price to pay.

But just look at 4:25, when there is nothing on the screen but the singer. What producer today would dare leave his star alone with only a pocket handkerchief?

Just look at how the orchestra is right there, not far from the singer (5:30). This show was a concert as much as a recording session – no mixing allowed.

Just listen at 6:15 when the singer does his thing a half beat off from the band. “Girls, come and kiss me…” He keeps his own rhythm and there’s no problem.

At the end of the song, just look. Just look at the immediate segue into “What Now My Love.” This was not a show for cut, cut, cutting. It was several little concerts.

The voice was flawless. It didn’t falter.

Now just look at 9:30 at his introduction to “Ol’ Man River.” He again moved directly from one song to another without a pause or a tape edit. He explained the song’s importance in the American repertoire, and in the span of a few seconds his persona shifted from entertainment superstar to black stevedore.

Listen to the words, the notes. Frank Sinatra respected the consonants as much as the feeling. Among all his recorded ballads, none was recorded or performed as perfectly as this one. He had put it on tape a few years earlier but, unlike most songs performed live, this rendition for television was at least as good because we can see it. We can see that the singer is acting as he’s singing.

Now just look at what happens starting at 12:30. “Tote that barge, lift that bale, you git a little drunk…and you lands…”

Here, at 12:36, Sinatra takes a breath.

“…in jail…”

The word extends, drifts south like the Mississippi, and then it deepens, and then the phrase lifts, still with the same breath.

“I gets weary…”

20 seconds later he inhales.

Not many wealthy white men from New Jersey could do what Frank Sinatra did with “Ol’ Man River” that October night in Burbank.

Enter the Queen of Jazz. From her aching, lilting “Body and Soul” she shifts quickly in mood to a racing, rousing rendition of Cole Porter’s “It’s All Right With Me.” Listen at 17:55 when she first exercises her glittering improvisational talent. And notice the orchestra supporting Ms. Fitzgerald during the next minute. Nelson Riddle was a master of helping vocalists to shine, and his arrangement here enhances both the singer and the song so that in an instant you can’t imagine it all coming together any other way.

By all accounts, Fitzgerald and Sinatra liked each other very much, and one gets the idea watching this video that he was in awe of her. At one point he literally sits on the floor and watches, beaming, while she riffs. Here Sinatra’s sexual edge doesn’t appear, as it often did with women.

This first of their two duets covered the range from Tin Pan Alley to rock. In it the singers managed “Up, Up And Away,” “Goin’ Out of My Head” and “Ode to Billie Joe” without compromising their dignity. The theme from Tony Rome made a blatantly commercial appearance; Sinatra’s film premiered a mere three days before the broadcast.

Sinatra’s patter with Fitzgerald in this part of the program included his praise of the music of the “kids today.” He seemed honest when he called the current music “groovy.” Presumably, then, he had experienced a philosophical conversion since 1957, when he wrote this:

My only deep sorrow is the unrelenting insistence of recording and motion picture companies upon purveying the most brutal, ugly, degenerate, vicious form of expression it has been my displeasure to hear—naturally I refer to the bulk of rock ‘n’ roll.

It fosters almost totally negative and destructive reactions in young people. It smells phony and false. It is sung, played and written for the most part by cretinous goons and by means of its almost imbecilic reiterations and sly, lewd—in plain fact dirty—lyrics, and as I said before, it manages to be the martial music of every sideburned delinquent on the face of the earth.

This rancid smelling aphrodisiac I deplore.

Indeed there had been a change of heart.

It would have been foolish for Frank Sinatra to do anything after Ella Fitzgerald’s portion of the show except change the pace dramatically – who could follow that? – and he did just that with the introduction of Antonio Carlos Jobim.

Jobim was credited as one of the originators of bossa nova and had been well known in jazz circles in the United States for several years, ever since his groundbreaking records with Stan Getz. It was his 1967 album with Sinatra, however, that introduced him to the American mainstream record-buying public. Francis Albert Sinatra & Antonio Carlos Jobim had featured both Jobim’s own compositions and standards from the American repertoire. Just listen to Irving Berlin’s “Change Partners” (28:35) and Cole Porter’s “I Concentrate on You” (30:45) as they had never before been realized. And then listen to “The Girl from Ipanema,” with Jobim taking a verse in Portuguese.

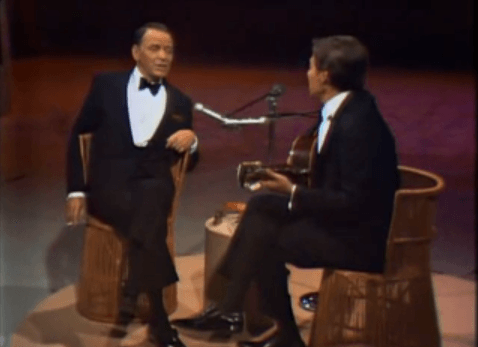

The characteristic we know as swagger was part of Sinatra’s stock-in-trade, a key element of his stage and screen persona. But this segment of “A Man and His Music” with Jobim showed him to be just as capable of intense anti-swagger. Two men in tuxedos simply sat in the dark in rattan chairs, gently and sophisticatedly making music. Look at Sinatra’s arm over the back of his chair at 33:00. Judging by his insouciance he might as well have been reading the newspaper in his kitchen. Several times during the medley he picked cigarette tobacco from his mouth, but not in such a way that audiences a half-century later would likely find offensive.

Aside from commercial breaks there were still 17 minutes to fill. To the benefit of you, me and generations hence, most of that time was occupied by another Sinatra-Fitzgerald duet. I have asserted that this show is Sinatra at his best; the last quarter-hour is the best of the show.

First was a quick jog through “The Song is You” (Oscar Hammerstein II & Jerome Kern), “They Can’t Take That Away From Me” (the Gershwins), and “Stompin’ at the Savoy,” which Benny Goodman had made a hit in 1934.

Then, at 36:50, just look at Sinatra tell Fitzgerald, “Go!” and sit down cross-legged like a kid at a campfire to watch her romp and growl and scat her way around the place. If you never heard of Ella Fitzgerald until five minutes ago, then the next minute and a half are all you need to know.

Sinatra takes Cole Porter’s “At Long Last Love” for a vigorous lap. “Is that Granada I see, or only Asbury Park?”

“Don’t Be That Way” (by Edgar Sampson, who also composed ‘Savoy” above), is lavished with Fitzgerald’s gale-force attention. After 43:00 listen to her “Honey, honey, honey, honey, don’t you cry,” and honey, you won’t even think of crying. Just look at Sinatra’s delight when he applauds her at 43:35.

“You’re on again” is Sinatra’s signal to Fitzgerald to commence with “The Lady is a Tramp.” The duet sizzles for 3 1/2 minutes and at 47:30 you think they’re done…but no. Sinatra signals Riddle for a coda. “She…likes…the…”

Downbeat.

“…green…grass…under her shoes…”

And the two take off again for another quick flight.

Frank Sinatra had two television variety shows of his own – both in the 50s – and neither was a success. Those cameras sometimes brought a kind of awkwardness from him. But not here. He and the cameras liked each other here. They lifted away the aura of menace that always seemed to envelop him. Tonight Frank Sinatra was more than someone to respect or admire. He was likable.

The show ends with bows from the guests, and with Sinatra singing what had been his unofficial theme song since radio days in the 1940s. “Put Your Dreams Away (For Another Day)” is a lovely and gentle way to say goodnight.

14 months later he would record “My Way,” which would become his anthem of backward-facingness. But on those three nights in October Frank Sinatra was a performer at his zenith. He was never better doing what he did.

THE BROADCAST

On Monday, November 13, 1967, NBC broadcast “A Man and His Music + Ella + Jobim” at 9 o’clock, following The Man from U.N.C.L.E and opposite The Andy Griffith Show, the #1-rated show on television. (“Aunt Bee and the Lecturer,” one hopes, didn’t steal too many viewers from the Sinatra special.)

You can buy a copy of this program here.