(Warning: Contains coarse language.)

The news last week brought word of the death of the retired Air Force General David Jones, who served as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the Carter and Reagan years. The newspaper obituary reminded me of a colorful moment during my days as a navy recruit.

Cold War-era US Navy boot camp was fun. It was fun because it was mostly easy for me and I took to military regimentation. Life is easy, after all, when somebody makes all your decisions for you. All you have to do is learn the rules and obey them. Stay in your own lane. Color inside the lines. Tote that barge and lift that bale. We spent most of our time learning about identification of rank insignia and the history of the navy and how to avoid venereal diseases while on shore leave. At the same time, though, boot camp was a little scary because I had goofed my way into what they called a Recruit Special Unit.

Rule Number One in the military, I’d been advised, was to keep a low profile and not volunteer for anything, and I generally did well by adhering to it. So, on the cold January night of my arrival at Naval Training Center Great Lakes, I did nothing except what I was specifically told to do.

“First you’ll fill in your last name. Now pick up your pencil. Fill in your last name. Put your pencil down. Next you’ll fill in your first name. Now pick up your pencil. Fill in your first name. Put your pencil down. Next you’ll fill in your social security number. Now pick up your pencil. Fill in your social security number. Put your pencil down. You don’t know your social security number? Give me ten pushups.”

It went like that for a couple of tedious hours, but then several guys with good posture came in bearing lots of adornment to their enlisted blue uniforms. White lace-up leggings on their ankles, gold silken ascot things around their necks and gold braid over one shoulder made for quite a sight at 3am in northern Illinois. They explained that they were part of the Recruit Special Unit, made up of a band, choir and rifle drill team that performed at each of the weekly graduation ceremonies.

Recruit Training Command Great Lakes was only one of the navy’s three installations churning out sailors to protect the American Way of Life. And every Friday afternoon, several hundred of them passed in review in front of their commanders and parents before heading off to more training or the fleet.

Boot camp lasted for eight weeks but the Special Unit, we heard, could keep you there a little while longer because it took several weeks to fill up each of those elite companies. The upside of these groups was that members were excused from “Shit Week,” during which recruits did nothing but grunt work: picking up garbage, shoveling snow, dishwashing, potato-peeling.

These duded-up swab jockeys handed out forms on which we were to indicate – after being given permission to pick up our pencils – whether we’d had any experience in band or choir or drill teaming. (I did.) Then there was a question at the bottom, asking if we wished to be part of the Recruit Special Unit. (I did not.)

That was that, I thought, but I was mistaken.

A day or two later, after we had been shorn, uniformed and injected with large tubes of various cillins, someone appeared before us with a clipboard. (An NCO with a clipboard almost never brings good news.) Names were called, mine among them. We were ordered to report to someone called Chief Ruzicka.

Moments later several of us found ourselves standing at sloppy attention before the desk of an unsmiling man wearing the insignia of a Chief Petty Officer (Musician specialty). With his Van Dyke beard he resembled Lenin, equally severe but with more hair.

The chief tapped a pencil on his desk with the regularity of a metronome – perhaps to the beat of a Sousa march in his head – and after several quiet minutes punctuated only by that tapping and by the ticking of a wall clock, he picked up a stack of papers and spoke.

“Which one of you is Miller?”

The guy standing next to me tensed up and answered, “Sir, here, sir!”

“I see that you played in your high school band…”

“Sir, yes, sir!”

“…but you say you don’t want to be part of our group.”

“Sir, yes, sir!”

“Why not?”

“Sir, I lost interest in band a while back.”

Chief’s head jerked up. “What? You WHAT? You lost interest in WHAT??”

His face reddened and he rose from his chair. He leaned forward at an angle that should have toppled him.

“What the FUCK happens if you lose interest in your job here? What the FUCK do you think happens if you get to the fleet and lose FUCKING INTEREST in your job there? Huh? What the FUCK do you think happens then??”

I don’t recall that he stopped to take in any air but spit sprayed generously with the consonants.

“How the FUCK do you think the navy is supposed to run if people get to the fleet and then LOSE FUCKING INTEREST? HUH?? How is that supposed to work? Go ahead and fucking TELL ME.”

He didn’t wait for an answer.

“Get out of here! Get the FUCK off my deck! You make me SICK! Get out, OUT!”

With one hand Chief Ruzicka pointed to the door and with his other he seemed on the verge of picking up his wooden swivel chair and throwing it at poor Miller but the recruit executed a fast about-face and scrammed.

Through the tirade I thought to myself with deep worry, “That’s what I was going to say.”

What would I tell the chief?

“Makes me fucking sick,” he muttered while gathering the papers that had blown off his desk during the explosion.

“Now…Russell.”

“Sir, here, sir!”

“Says here you played trombone in junior high and high school but you don’t want to play here. Why not?”

Through my tremors I heard a muse sing.

“I…didn’t think I’d still be good enough, sir. It’s been a few years.”

I felt proud but managed to suppress a smirk.

“Aw, you never know. How about you give it a try and let’s see how you sound?”

“Sir, of course, sir!”

He sent me into a rehearsal room where I found a trombone that appeared to date from the era when Lieutenant Commander Sousa himself directed the band at Great Lakes. Sheet music for “Anchors Aweigh” was on the chairs so I honked out a few bars and played scales. Several other guys straggled into the room and found instruments for themselves.

After ten minutes or so the Chief came in.

“OK. Let’s have a listen. You go first.” I was up.

After 30 seconds of “Anchors Aweigh” he stopped me. The sounds coming from the end of my horn could have attracted rutting moose all the way from Wisconsin and I envisioned a quick “Thanks but no thanks.” I was, however, in for a surprise.

“You see? That wasn’t so bad, now, was it? What do you say? How about coming aboard?”

“Of course, sir.”

And so it was that eight weeks of basic training turned for me into eleven weeks. Company 909, like most military units, came up with a name for itself. “Futch’s Finest” hadn’t quite the ring of, say, the Big Red One, but when your company commander is named Woody Futch the options are limited.

Our group performed for three successive Friday ceremonies, at the last of which we ourselves graduated.

One notable member of Futch’s Finest was a professional saxophonist named Charlie Young. He’d toured with Natalie Cole and was the regular replacement on The Tonight Show when saxophonist Tommy Newsom stepped out to lead the band in Doc Severinsen’s absence.

Charlie had won a slot in the US Navy Jazz Band, based in Washington. It was (and is) one of the most elite musical ensembles of the American armed forces, but first Charlie had to go through boot camp just like everyone else in the service. A dashing 30-something African-American with mean musical chops, he played jaw-dropping solos in all of our performances.

In the winter all drill instruction and PT – as well as the graduation ceremonies – took place in hangar-like buildings called Drill Halls. Roughly the size of an aircraft carrier’s deck, each of the dozen or so of these monsters kept Great Lakes functioning all year long.

Every Friday there were two special guests in attendance: a senior officer to give remarks and oversee the “Pass in Review” and a guest of honor who was a long-serving NCO or decorated veteran or even a prominent civilian with ties to the navy or the base itself.

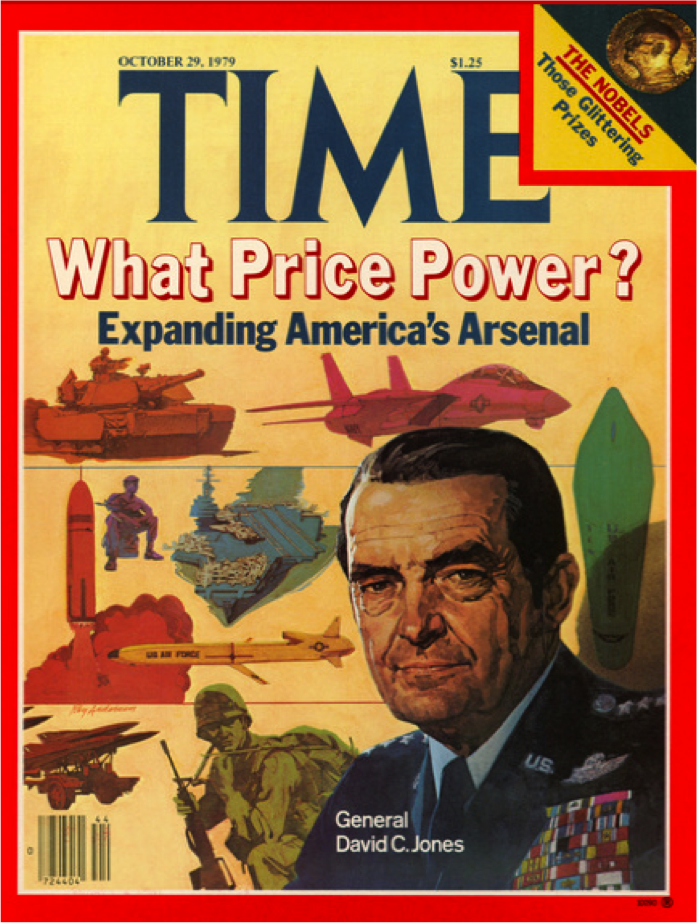

One week we were honored by the presence of General David Jones, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. His was a name we all knew very well from the Chain of Command we had to memorize. From Platoon Leader all the way to President, we either produced the correct names when asked or did pushups as penance. General Jones was a tall, imposing figure.

The other guest that week was Captain Joan Bynum, a distinguished nurse who was the first black woman in the history of the US Navy to achieve that rank.

Predictably, our musical program included the “Star Spangled Banner” and of course “Anchors Aweigh,” but less probably, we played the theme from “Jesus Christ, Superstar.” I don’t know why. It was in that number that Charlie Young had his two minutes to riff. He’d step forward and let loose, and he always brought the house down.

While Charlie rocked on his tenor sax, I noticed that Captain Bynum was – how to say? – enjoying his playing very much. Even sitting next to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs – her nation’s highest-ranking military officer – she writhed and wiggled. Her hips jerked subtly in her chair as she clapped in time with the music.

When Charlie finished his cadenza Captain Bynum leapt up to applaud but in her excitement she lost her footing. Both she and her chair flipped backwards, and our view from the band was of the soles of a pair of regulation black pumps. Blessedly, I have no memory of whether or not I also glimpsed Captain Bynum’s undergarments from my vantage point.

General Jones bent over to help Captain Bynum to her feet and order was quickly restored on the reviewing stand. The graduation ceremony resumed without incident but I suspect that Captain Bynum remembered it for a very long time.