I’ve heard it said that a scar adds character to a man, perhaps because it implies adventure, danger, a past. I don’t think of myself as having led a particularly adventurous or dangerous life, nor do I have a capital-p Past. I do, however, like to believe I’m a man of a certain character, but I’ll leave it to history or some future biographer to determine to what extent that might be related to the scars on my body and to what extent it’s a good thing.

My oldest scar dates to around 1966, in Houston. My parents and brother and I had gone out for dinner, possibly to Wyatt’s cafeteria in Sharpstown Mall. I liked going to Wyatt’s because my sweet tooth was indulged there, though more so on after-church visits than at weeknight meals, and although I never finished the multiple desserts I was allowed I continued to be allowed them.

As we pulled into the driveway at 6014 Moonmist, Daddy was driving, Mama rode shotgun, Randy was on the left side of the back seat, and I sat behind Mama. This seating arrangement was relevant to what soon transpired.

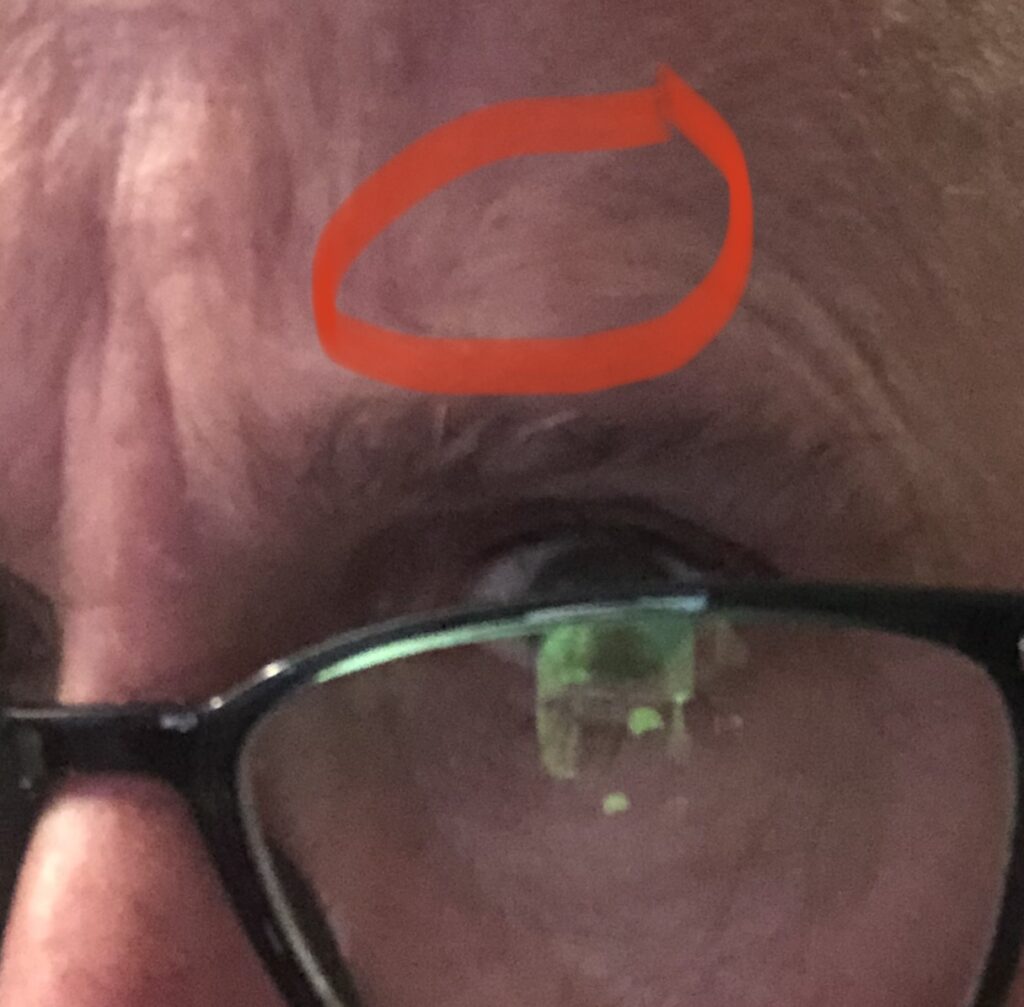

Mama stepped out of the car to open the garage door. I, for some reason, had stuck my head out of the back window like an Irish Setter or one of the larger spaniels might. I had stuck my head out far enough that when Mama closed her door it caught the skin over my left eyebrow. At this moment I learned a Lesson for Life, namely that wounds on the head result in much bleeding.

As I bled and Mama shrieked, the two of us got back in the car, Daddy and Randy still in it, and headed to the Emergency Room. The hospital happened to be across the street from Sharpstown Mall, which means that if in fact we’d had dinner at Wyatt’s that evening it would have been more convenient, driving-wise, if Mama had slammed the car door on my head at dinnertime, rather than afterwards in our driveway.

In addition to the realization about blood loss resulting from head wounds, that evening I learned a new meaning for the word “stitch.” I had heard of stitches because one of my grandmothers was an avid embroiderer and seamstress. I knew they involved needles and thread. I knew the reason my grandmother used a thimble.

I was therefore alarmed to learn that I was to have some of these “stitches” applied to my own body. Mama’s shrieking had subsided and she tried to reassure me. “It won’t hurt a bit,” she said through a twitchy half-smile. Her reassurances mattered little, however, when I observed through my five-year-old eyes that the needle intended to close my wound resembled less the ones my grandmother used for crewel work and more those my mother used for knitting.

I went home with three stitches that night. I think they gave me a sucker when we left.

I don’t assign Mama any blame for the incident because there would be no reason, when stepping out of a car to open the garage door, to look back and make sure the kindergartner in the back seat hadn’t inserted his head into the swinging path of the car door.

Moving along chronologically, we come to my period of model rocketry, which would have been around the sixth or seventh grade. I’d build a rocket, my dad or brother would take me to a field somewhere, and I’d fire the rocket. I recall enjoying the construction phase more than the blastoff itself. This could be due to my apprehension about the engines, which resembled shotgun shells.

Model rocket construction is fairly straightforward. In its simplest form, there’s the body tube with fins at the bottom, and a nose cone. At the high point of the flight, the nose cone pops out and deploys a parachute.

Some rockets, including the one that resulted in a scar, have a more complicated design. My V-2 replica had a tail cone in addition to the nose cone. I had admired the sleek design of the V-2 without knowing, as I know now, that it was the first long-range guided ballistic missile, designed and used by the Nazis specifically to attack cities.

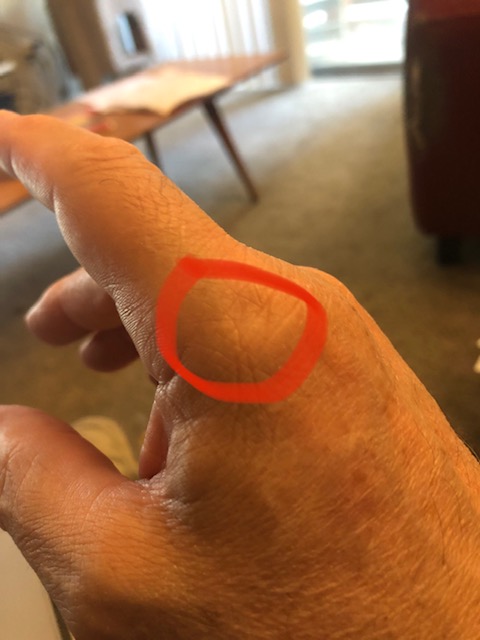

Thinking of myself as an advanced-level rocketeer, I did not always read assembly instructions, as was the case when I glued the tail cone into the wrong end of my V-2. In an effort to salvage the model, I took to the offending joint with an X-Acto knife.

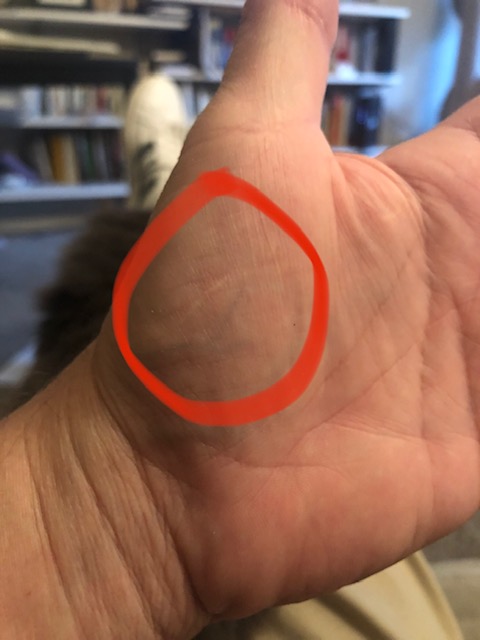

With the rocket in my left hand and the knife in my right, I began to cut and pry loose the cardboard tube from the plastic tail cone. I proceeded with delicacy so as not to damage the body irreparably, but with apparently insufficient delicacy, considering that the X-Acto blade ripped through the cardboard and entered my left hand, specifically the meaty part between the thumb and wrist.

There was blood but no shrieking by Mama. No stitches were required.

A few years later, in July 1978, my brother got married in Dallas. The evening of the wedding, the bride and groom having left on their honeymoon, Mama and Daddy and I, along with some other relatives, were in our motel. The motel had a pool and the pool had a slide.

Sliding down a swimming-pool slide in an upright position is a pleasant enough experience on a warm summer night in Texas. I decided, however, to improve on the experience by sliding down the slide in the prone position, headfirst.

Hindsight brought me enlightenment as to swimming-pool slides. Hindsight taught me that sliding headfirst down one of them is a bad idea.

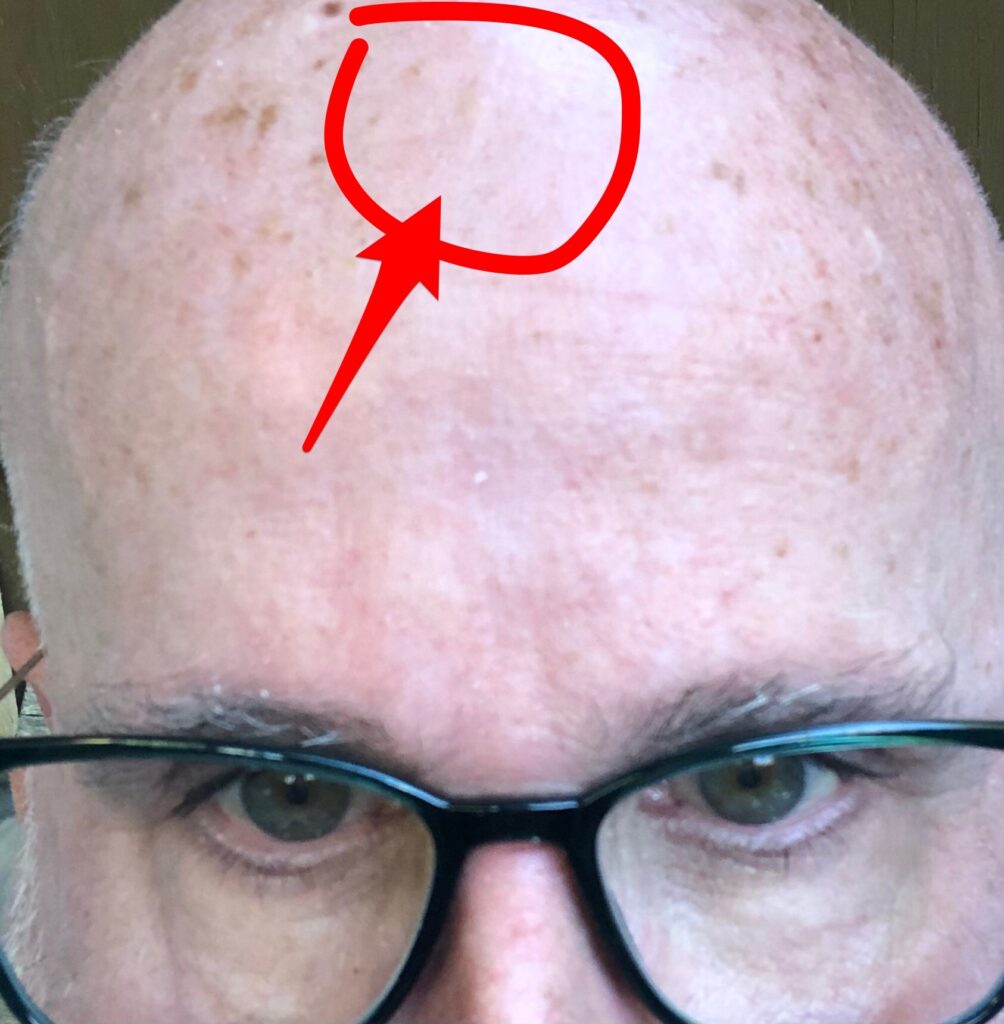

That realization struck me approximately three seconds after embarking upon my first prone-position journey down the slide, when my head struck the bottom of the pool with a resonant “clunk.” The water around me took on a pinkish cast.

I clambered dizzily from the pool. Seeing my stagger and the crimson torrent over my face, Mama and Daddy rushed to my aid, escorted me into the motel room, which was at pool-level, and bent me over the sink. We had something of a suite, with two bedrooms sharing a living room, and the sink into which I bled was in that living room, I suppose intended as a bar sink.

Head-dabbing with towels ensued and the bleeding subsided. The scar remains.

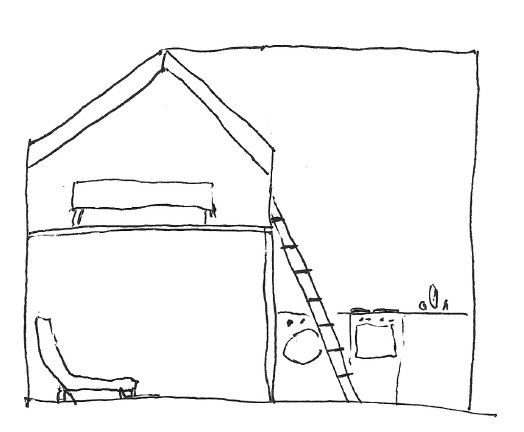

Jumping ahead, out of the order of scar acquisition, I recall May 2003, when Calvin and I spent a week in Paris. Many French apartments offered as vacation rentals make use of their tiny floor space by creating a loft sleeping area, accessed via a ladder. The ladders are not entirely vertical, but they’re not far from vertical. Our apartment was on Rue de Renard, a few steps from the Hôtel de Ville, or Paris City Hall.

There was a well-equipped kitchen, and one of those loft sleeping areas. The ceiling above the bed was peaked, leading you to imagine you were sleeping in a tent or an attic. The bed was comfortable.

There were exposed wooden beams on the ceiling over the bed, about four feet above the bed at the peak and less at the sides, and as Calvin and I first sat ourselves upon that bed, after climbing the not-quite-vertical ladder, I looked upward and said, “Before this week is over, I’m going to hit my head on the ceiling.”

It took seven days for my premonition to come true, but come true it did.

On our last morning in the City of Lights I awoke from a sleep of well-fed, touristy satisfaction, and sat up on the side of the bed, as people tend to do when they wake up and intend to get out of bed to start their day.

My premonition came true just at that moment. I sat up on the side of the bed and hit my head on the exposed beam. There was a resonant “clunk,” and I snatched a nearby pair of underwear to dab the bleeding across my face of which I was quickly becoming aware.

I clambered down the stairs, being careful not to spew blood on the carpet. Bloody carpet might have jeopardized the security deposit that Calvin and I had used to rent our apartment.

We needed to leave for the airport, to go home to California, in an hour or so, and although the nature of the wound on my head was such that I should best have seen a doctor, there was no feasible option rather than to stop the bleeding with toilet paper and throw a baseball cap on my head.

This wound did not, strictly speaking, produce a scar because the injury occurred at precisely the same spot as the brother’s-wedding-night-swimming-pool-slide injury. But the events of Paris enhanced what was already there.

At Charles de Gaulle airport a few hours after the accident, a security officer performed pre-checks ahead of the x-Ray area. She looked at my passport and asked me to remove my cap. I said, “OK but it’s not pretty.”

She recoiled at the sight of my gash and waved me along.

Moving ahead to 1980—or moving back in relation to the Paris incident—my summer job was on a highway construction site, where I was a rodman on a survey crew. We’d drive around and mark points in the ground where roadways, retaining walls and piers for bridges would go. These points were usually marked with two-by-two stakes that were pointy at one end, like the stakes you see in Dracula movies. We’d pound the stakes where the surveyor told us to, using a sledgehammer.

The ground in San Antonio in the summer could be rock-hard, and for really obstinate pieces of earth we’d use foot-long stakes made of iron. I had thought they were steel, but the doctor who tried to extricate a piece of one of them from my right hand, after it had chipped off during a pounding session, told me it was iron. He knew this because the little magnet-thingy with which he was poking around inside the wound didn’t retrieve anything. He said iron wasn’t magnetic, which doesn’t make any sense now that I think about it. Maybe he just wasn’t very good at extricating shards of metal from people’s hands.

In this case I carry both scar and shrapnel.

Another couple of years hence, I was Seaman Russell, USN. At Great Lakes Naval Training Center, where I was occupied with obstructing Soviet submarine attacks on Chicago, there is snow. It is natural for people to want to romp in snow or otherwise play with it, but the United States Navy, via its authorized representatives of higher rank than myself, suggested in urgent tones that romping or playing-with was discouraged. Harming oneself with snow-romping would in effect be damaging government property, an activity on which the Department of Defense frowned and for which it would punish.

I lived in a dorm-like environment. The two-man rooms in the cinder-block building had bunk beds and linoleum floors. Everything was ecru.

One winter’s day, with temperatures in the teens and snow on the ground, a group of us gobs had assembled in my second-floor room. I don’t just now remember why everyone was in my room, but I assume these 40 years later that it was because I was then, as now, a gracious and entertaining host.

We gobs decided it would be a good idea to have a snowball fight there in my room. With no snow in the room itself, we opened the window, extended our arms outside, and gathered some from the windowsill. The snowball fight lasted only a moment or so. It was cut short when one of my fellow sailors reached outside, scooped a handful of Illinois snow, cupped the snow into a ball, and tossed it at me.

Seated at my desk, I leaned down out of the line of fire of the snowball. The snowball indeed sailed over my head, but my head connected with force with the corner of my desk. It didn’t hurt much but I soon became aware of liquid cascading down my face. A quick inspection indicated the liquid was blood.

I held a t-shirt to the wound and went downstairs to the duty officer’s office. It was a weekend, and a senior non-commissioned officer was always there to keep us from killing ourselves before Monday morning. There was a quite-sophisticated hospital on the base, and a duty driver was summoned to take me there. At the Emergency Room, I was asked how my injury occurred, and in that moment I committed what I believe was the only punishable offense of my time in the military.

I said to the corpsman, “I was sitting at my desk and dropped my pencil, and when I leaned over to pick it up, my head hit the corner of the desk.” The statement was half-true.

The corpsman, who had been taking notes, stopped writing and looked at me with incredulity and pity. “How stupid can you be,” he surely thought. “I hope you aren’t going to be involved with weapons or nuclear energy,” he thought.

A disposable razor was produced, and the corpsman shaved an inch-and-a-half circle around the wound, and a physician came in to insert two stitches.

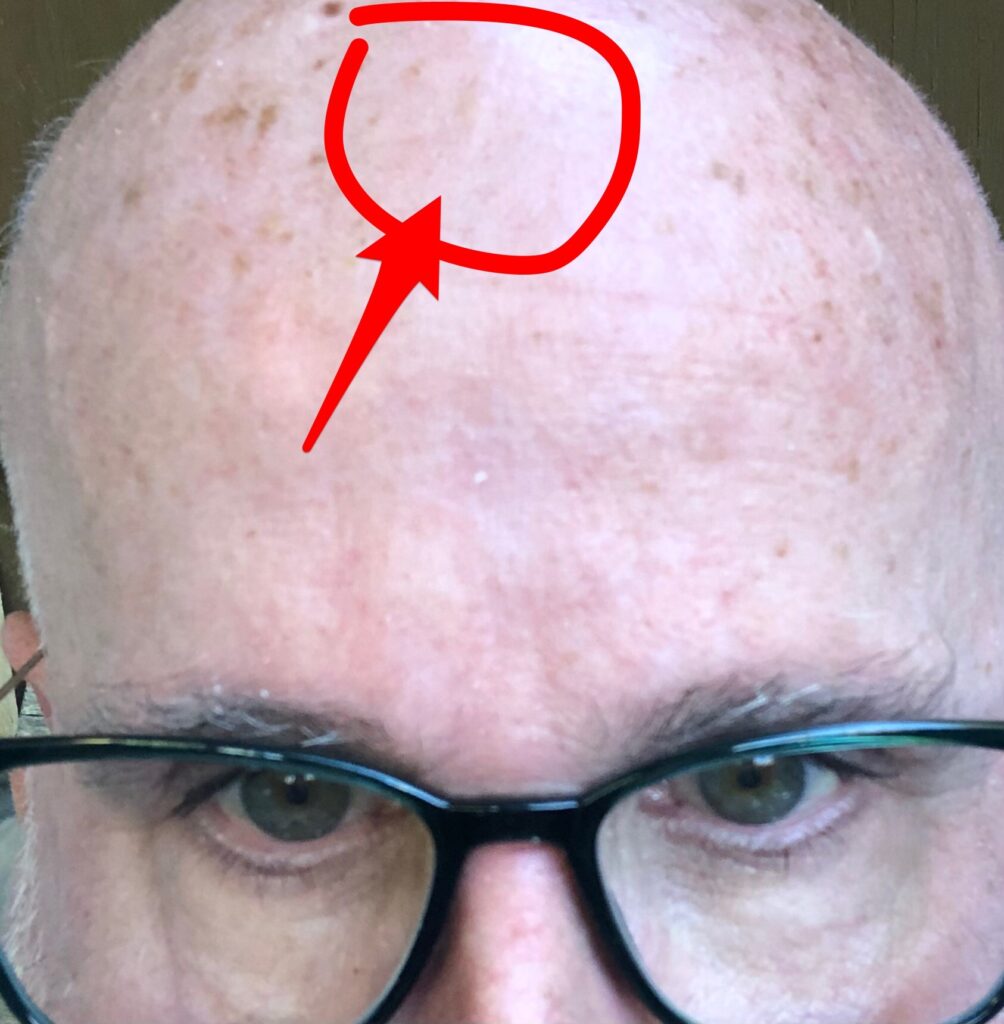

From my naval service I retain my honorable discharge—two, actually, but that’s a long story—and a little L-shaped scar an inch or so above what used to be my hairline.

1983

A 1975 Triumph TR-6 (yellow).

Working on carburetor.

Flat-head screwdriver in palm of left hand.

1987

Chicago. Marshall Field & Company’s Water Tower Place store. Men’s shoe stockroom.

There was a device we used to retrieve shoe boxes from high shelves. Called a shoe pick, it was essentially a broom handle with an L-shaped plate at the end. You’d insert the top of the L beneath the shoe box lid, and slip the bottom of the L under the box. In theory this would allow you to slide the shoe box from its shelf and lower it safely to you.

But the fact of the matter of shoe boxes is that they’re shitty. Their lids break if you look at them sideways. And the lid of a particular Polo Ralph Lauren shoe box at Marshall Field’s in 1987 broke as I slid the box from the shelf. The shoes tumbled down upon me, in the process knocking the pick from my hand. The business end of the pick, amid the torrent of shoes, gouged my right hand. There was remarkably little blood, but it was the first time I had ever laid eyes on one of the bones in my body.

Off I trudged to Northwestern Memorial Hospital’s Emergency Room for a tetanus shot and two stitches.

2001

Pacific Palisades. Cooking in a private client’s home.

Salmon.

Flipping salmon.

Too vigorous.

Hot oil splash.

Burn scar.

2022

Placerville.

Removing baking sheet from oven with right hand.

Baking sheet hot.

Baking sheet meets left forearm.

Burn scar.

CATS

Through the years and across my decades of cat-ownership there have been occasional periods during which flea baths have been necessary (for the cats). In no instance were the cats who required flea baths happy about the flea baths. On the contrary, they struggled and resisted.

I loved my cats very much, and I look at the scars they left me as souvenirs of loving relationships rather than remnants of evil.

The point of all this is to suggest that a physical scar is a kind of punctuation mark in a life, but I don’t have a way of knowing whether I’ve been punctuated more than most. Anyway, I’m still here. And I’m not ready to think I won’t be punctuated some more.