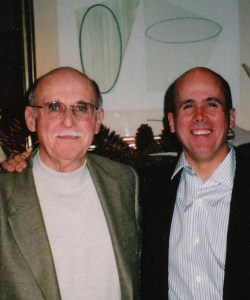

I live far away from Jim Russell geographically but we trade emails a lot and we talk now and then and I think of him all the time. He’s on my mind because I know that much of me is him and because he gave me many of my happiest memories.

I inherited or absorbed Daddy’s fondness for groan-inducing jokes. There’s one, the body of which I’ll spare you, whose punch line is “transporting gulls across a staid lion for immortal porpoises.”

Often, on drives up to Canyon Lake in the Hill Country, he’d pull out a chestnut.

“I wonder if they ever found that Indian?”

“What Indian?”

“The one they’re looking for.”

“What are you talking about?”

“The missing Indian.”

“What missing Indian?”

“Didn’t you see the sign?”

“What sign?”

“We just passed it. Didn’t you see it?”

“What sign?”

“Right back there. ‘Watch for Falling Rock.’ That Chief Falling Rock sure has been gone a long time.”

That’s how Daddy is.

He liked to cook and he participated in my early kitchen adventures as much as my mother did. After I came home from a 1972 road trip across the South with Mama and her mother, bringing with me a box of Cafe du Monde beignet mix from New Orleans, Daddy helped me to roll it, cut it into rectangles, and do my first deep-frying. I believe it was Mama who had to clean up the greasy, powdered-sugar-y gunk from the stove and counters and floor afterwards.

Daddy showed me how to gut and scale a fish, though that need would have arisen more if we had done a better job of tying stringers to the dock. We lost some perch, crappies and flounder along the way.

Daddy had two ways of acknowledging nearby flatulence, though generally only among family and friends. “Guilty man speaks first” was his response if I were to comment on a smell, and if the event was audible he’d say, “I think I heard a buck snort.” (I said “had,” but for all I know he still does this.)

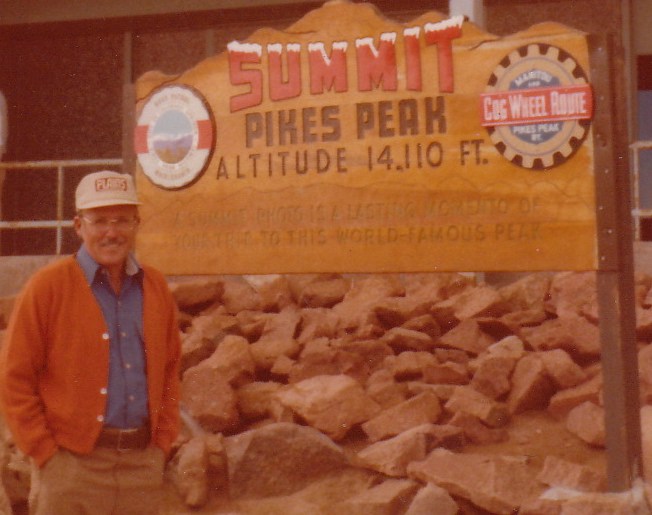

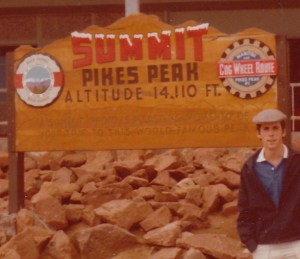

Daddy encouraged me even when it distressed him, such as on our trip to Colorado a month after I got my driver’s license. We went a couple of times to Rocky Mountain National Park, Daddy and I, to fish for trout and to eat the doughnuts at the visitor center at the top of Trail Ridge Road, which are among the best doughnuts I’ve ever eaten. (Those from the snack bar at the top of the Eiffel Tower are very good, too, but they call them “dounoughts” there.)

On this particular trip to Colorado we made a stop at Pike’s Peak and decided to drive to the top rather than spend money on the railway or whatever conveyance they had. My memory of the road to the top of Pike’s Peak…

(Is that duplicative – “top of Pike’s Peak”? I guess not, since Pike’s Peak refers to the entire mountain, though there is a case to be made that the naming authority should make things clearer.)

The road up Pike’s Peak, as I recall it, was barely 15 feet wide and it was unpaved. It was a narrow gravel road over which you had to drive if you wanted to save money by not taking the public conveyance. There was no shoulder on the road up Pike’s Peak; about six inches from the edge the road disappeared into Rocky Mountain oblivion. In Texas, if a road passed over a drainage culvert a foot deep, you’d see foot-wide wooden pylons banded together by heavy strips of steel. Driving in Texas was like doing bumper cars; you just had to intend to stay in your lane and the barricades on the right would do much of the work. Not so in Colorado.

In Colorado the driver of a motor vehicle, especially on the road up Pike’s Peak, bore all the responsibility for staying in his lane. As a new driver I made a solid effort to this end but Daddy, occupying the co-pilot’s seat, saw only the few inches of safety between his side of the car and a dropoff equal roughly to the height of a Sears Tower or two. His mantra on that drive was, “Stay left! Keep left!”

I tried to oblige but in the cars heading down the mountain, or “peak,” were drivers who clearly wished to take advantage of their entire lane and not just five feet of it. Those drivers, as they encountered our blue Chrysler Newport with a white vinyl roof, waved vigorously at me as if they were attempting to put out a fire. Their waves indicated not so much expressions of welcome as a hope that I would direct our car somewhat to the right.

“Keep left,” Daddy urged.

“They’re waving at me,” I replied.

“I don’t care. Stay left.” I’m sure that Daddy didn’t doubt what I was reporting to him but his nose was pressed to the glass, his eyes aimed into the abyss. “Stay in the middle.”

We arrived at the peak of the peak and looked around some. The doughnuts up there weren’t as good as the National Park doughnuts I mentioned earlier. The downhill drive was less torturous.

Daddy and I have had a lot of fun together but there was one particular time when he did something for me that elevated him to hero status.

In junior year of high school we students began in earnest to do what was called “creative writing.” After taking several tests involving essay-composition we were shown the tests, with the grades on them. But then the teacher re-collected them.

“Don’t we get to keep them?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“You just don’t.”

This didn’t sit well with me so I wrote a letter to the superintendent of the district. A couple of exchanges later, the result was that I would indeed receive my papers back at the end of the school year.

Well, when the end of the school year came I asked the teacher for my papers but she wouldn’t oblige. “I haven’t been told to give them to you.” (There was a certain irony in her response, considering that she had emphasized the use of the active voice in every possible situation.) So I wrote another letter to the superintendent, who replied to the effect that yes, my papers would be returned to me.

A week later, the head of the English department came into my class and asked to see me. I did not know this woman personally but knew my mother’s opinion of her, and my mother’s opinion of Mrs. Everidge was not especially high. (Mama taught at my high school.)

Mrs. Everidge, it seemed, was not pleased about the situation involving my papers and the letters to the superintendent. “I don’t know what you thought you were doing,” she hissed. “We have ways of doing things.”

“Yes, but I disagreed with them so I wrote a letter. And I’d like to talk to my mother. Her classroom is right around the corner.”

“I don’t know. Maybe I’ll let you talk to her.”

Mrs. Everidge, it turned out, was leading me to the assistant principal’s office. Past the attendance desk we went and into his office. Daddy was already there, waiting. “Uh, hi,” I said.

“Hi, Clay,” Daddy said.

Assistant principal explained that I had written some letters and gotten the superintendent involved.

“I know that,” Daddy said.

“Mrs. Everidge here is chair of the English department, you see, and we have policies intended to…”

He buzzed and droned for a couple of minutes. Daddy and I sat and stared.

When the assistant principal finished his sermon there was silence. Mrs. Everidge puffed a bit; she was proud.

Daddy was expressionless, and this was where he became my hero. “So when does Clay get his papers back?”

Mrs. Everidge deflated like a basketball with a hole in it.

“At the end of the last day of classes.”

“Thank you,” Daddy said as he stood up. “Clay, you can go back to your class.”

He and I walked out of the assistant principal’s office and said good-bye to each other. For the life of me I don’t think we spent more than a minute at dinner that night discussing the whole thing. It was done, handled. Daddy had my back that day and I never forgot it.

One more thing that Calvin just reminded me of after reading a draft of this post: After Calvin’s father died in 1998, Daddy said to him, “If you ever need someone to talk to, you can always call me if you need fatherly advice. You can always call me ‘dad.'” That was a pretty fantastic thing to do.